The Internet, The News, &

The End of Kids Playing Outside

Tracy Markle, MA, LPC &

Dr. Brett Kennedy, Psy.D.

In This Article

Kids playing outside used to be a common sight. But today it’s becoming exceedingly rare. In the US, studies show that parents are fearful of allowing children to play outside unsupervised despite the fact that there’s never been a safer time to grow up. That’s right. There’s never been a safer time. Why does that sound wrong? One answer might be our constant access to news. News that researchers have correlated with higher stress and a misconception that the world is more dangerous than ever. The result is that parents are giving children cellphones at younger and younger ages and children are filling their rare free time with online activities and missing out on play in nature that’s crucial to their development. How can families sort through unfounded worries and recognize when it’s okay to give kids their independent mobility? Read on to learn.

The Cellphone as Peace of Mind

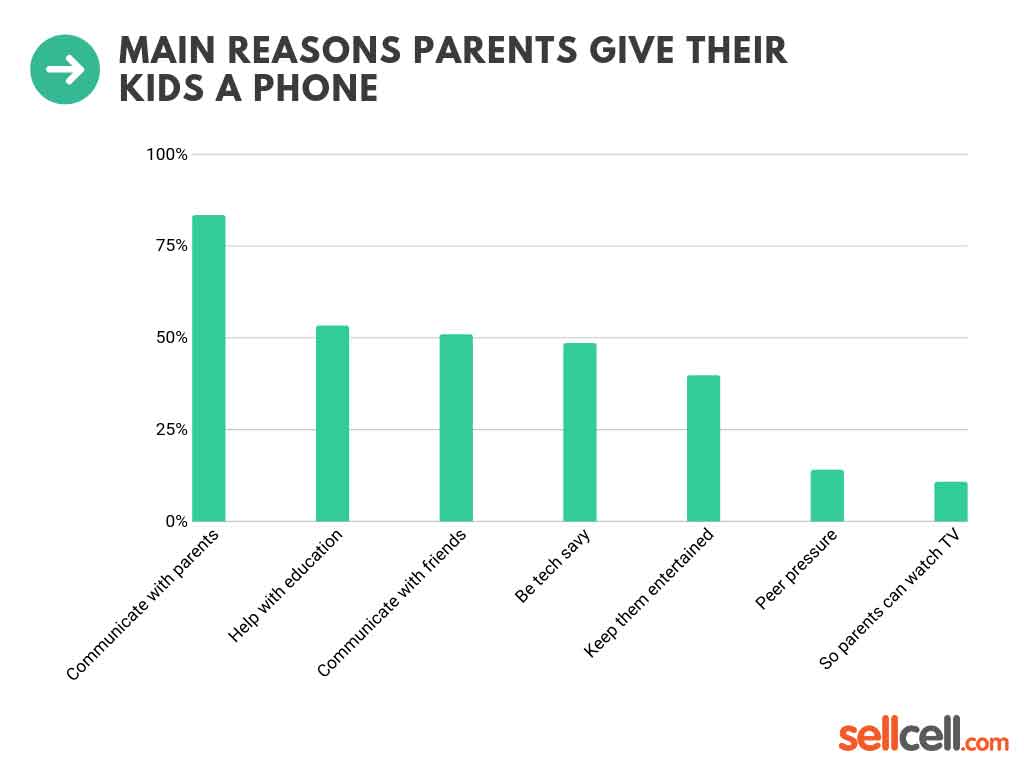

Parents might worry about what could happen to their child when they go online, but fear of what could happen to them offline seems to worry them more. Surveys show that the majority of parents cite constant connectivity with their children, as well as “safety and peace of mind” as the top reasons they allow them to have cellphones.1,2,3

School security experts also report that parents have continually lobbied school boards to allow cellphones in schools primarily based on the argument that phones will make students and schools safer in light of tragedies like mass school shootings.4

A 2018 poll by the professional association for educators Phi Delta Kappa International (PDK) found that 1 in 3 parents believe their child is physically unsafe at school.5 PDK reports that this level of parental concern represents a twenty-year high and is a steep increase from 2013 when just 12% of parents were fearful.

Child's First Cellphone: How Young Are They?

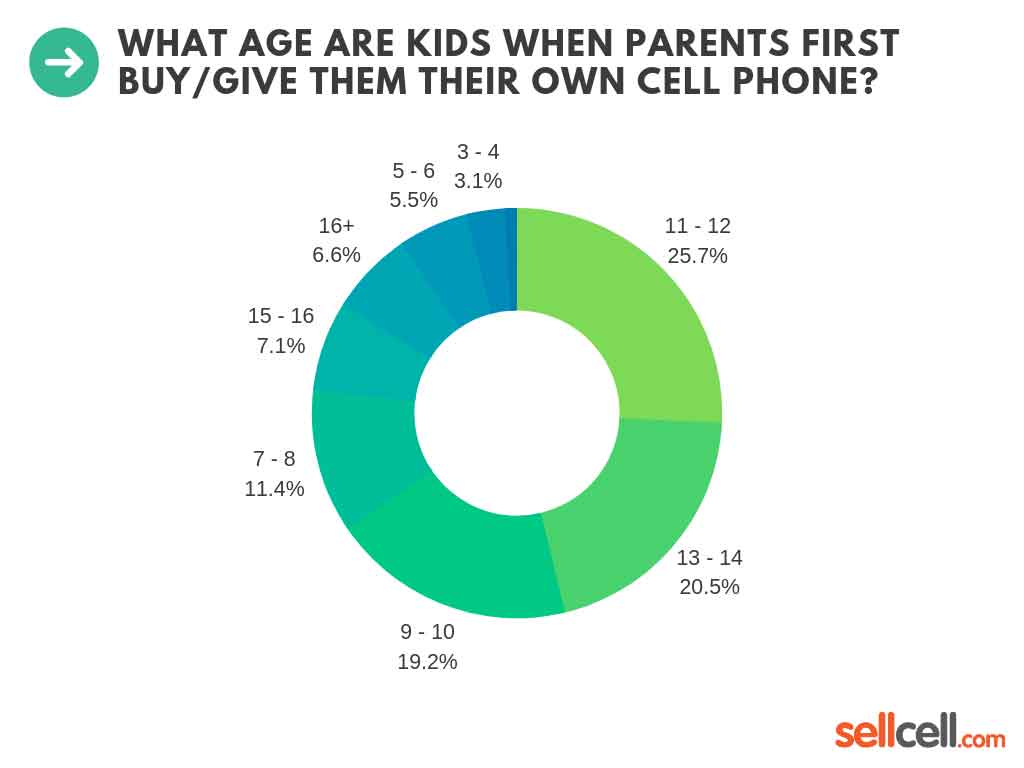

A 2019 survey of more than 1000 US parents conducted by tech trade-in site SellCell revealed that 11 to 12 is the most popular age range for children to receive their first cellphone, though ages 9 to 10 and 12 to 13 are also popular.6 11.4% of children receive a cellphone between the ages of 7 and 8 and the youngest age range parents report giving their child a cellphone is 3 to 4. All told, 65% of US kids under the age of 13 now have their own cellphone.

Slightly increasing these results is a survey conducted the same year by Common Sense Media which found that 69% of kids have a cellphone by age 12.7

The same year that these surveys were conducted, a worldwide survey of more than 9,000 parents by cybersecurity firm Kaspersky found that 84% of parents are worried about their child’s online safety and a US survey by PCMag found that 76% of parents are worried about their kids’ online safety. 8, 9

Is it really more dangerous for kids playing outside today?

As it happens, there’s never been a safer time to grow up in the United States.

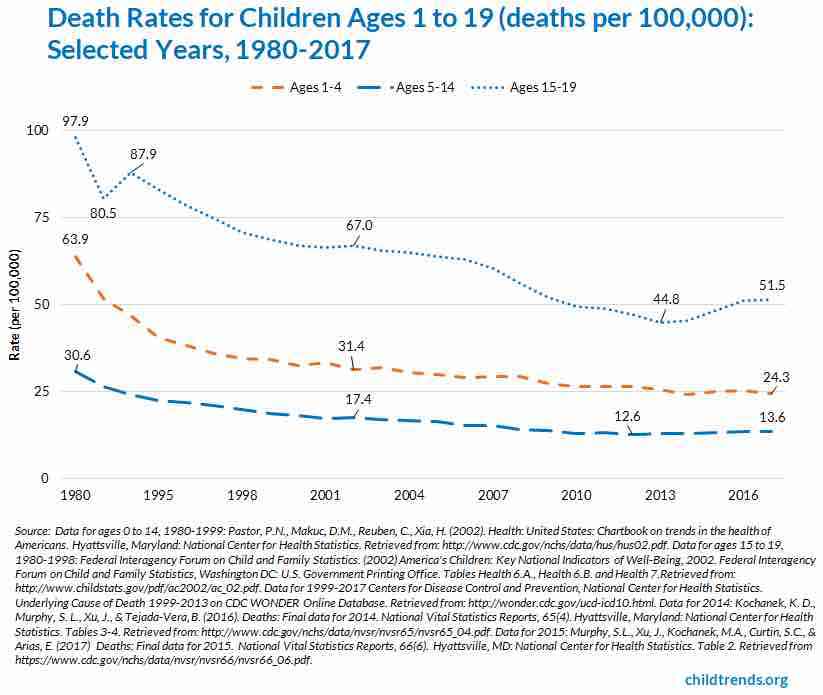

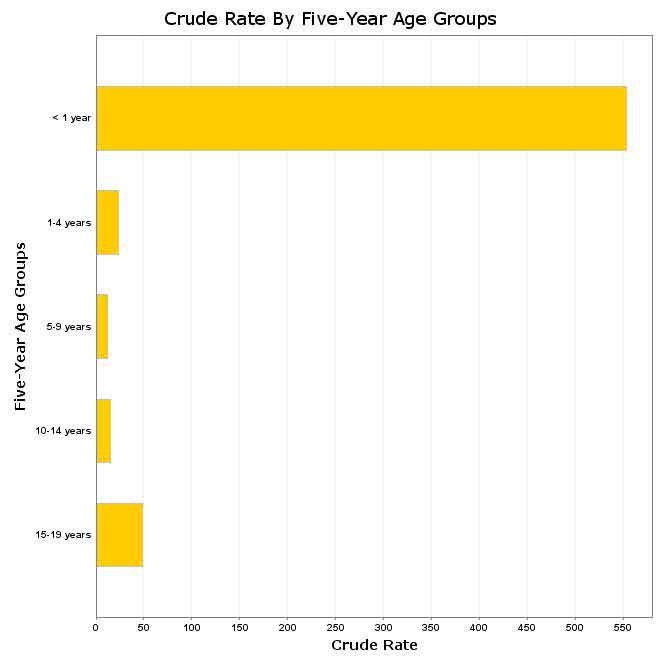

Death rates for children have fallen dramatically since 1980.10,11 From 1980 to 2017, death rates for children ages 1 to 4 dropped from 63.9 to 24.3 per 100,000. Death rates for children ages 5 to 14 dropped from 30.6 to 13.6 per 100,000. Death rates for teens ages 15 to 19 also declined from 97.9 per 100,000 in 1980 to 51.5 per 100,000 in 2017.

In fact, a child is more likely to die in their first year of life than they are during any other time in childhood.12 For example, in 2019, children under age 1 died at a rate 11 times higher than children ages 15 to 19, the age group with the next-highest mortality rate (553 and 48.7 per 100,000, respectively).13

But what about mass shootings at schools and other public places? Are they happening more frequently?

In a study published in 2018, researchers at Northeastern University found that the risk of being killed in a deadly and indiscriminate massacre is exceptionally low.14

And that shooting incidents involving students have been declining since the 1990s.15

In December of 2021, one of the study’s authors, criminologist James Alan Fox, citing the Associated Press, USA Today and the Northeastern University mass killing database, tweeted, “Since 2006, there have been 11 mass killings (4+ victim fatalities), all by gunfire, at schools”.16

Since 2006, there have been 11 mass killings (4+ victim fatalities), all by gunfire, at schools — 6 at K-12 and 5 at colleges, according to the @ap, @USATODAY, @Northeastern University mass killing database.

— James Alan Fox (@jamesalanfox) December 2, 2021Image 1: James Alan Fox, Criminologist at Northeastern University and member of the USA TODAY Board of Contributors, tweeted about the number of mass killings in schools in 2021.

Do Cellphones Keep Kids Safer During a School Crisis?

Statistics show that the risk of being killed in a deadly and indiscriminate massacre is exceptionally low. But if a child were to find themselves in that unlikely situation, what do school safety experts say about student cellphone use in a school crisis?

It turns out that when hundreds or thousands of students try to use their cellphones at the same time during a crisis, the network can become overloaded and rendered useless.17

That’s what National School Safety & Security Services, an Ohio-based school safety consulting firm says. They are often asked to weigh in on the debate about whether the distraction cellphones can pose for students in school outweighs the perceived security benefit.

While they do recommend cellphones for school administrators and crisis team members as a crisis management tool, they list multiple reasons on their website why student cellphone use can actually hinder school safety:

5 Reasons Cellphones Can Hinder School Safety

- In a number of cases nationwide, bomb threats have been called into schools by students on cellphones. In a national study by the firm of more than 800 school shooting and bomb threats, researchers found that 37% were sent electronically using social media, email, text messaging and other online resources, prompting researchers to conclude that electronic devices and social media apps are fueling the growth of these threats.18 While the vast majority of threats turned out to be hoaxes, each one had to be seriously investigated. This resulted in loss of classroom time, wasted police resources, frightened children, and alarmed parents.

- In the presence of an actual explosive device, public safety officials typically advise school officials not to use cell phones, two-way radios, or similar communications devices because they present some risk for potentially detonating the device.

- It’s probable that hundreds or thousands of students rushing to use their cellphones in a crisis would overload the cellphone system and render it useless. In this case, the use of cellphones by students could conceivably decrease, not increase, school safety during a crisis.

- Cellphone use, texting, and other outside communications by students during a crisis causes parents to quickly gather at the school at a time when school and public safety officials may need parents to stay away from the school site due to evacuations, emergency response, and/or other tactical or safety reasons. This could delay or hinder parent-student reunification. In extreme situations, parents could find themselves in harm’s way.

- Cellphone use accelerates the spread of misinformation, rumors, and fear. These rumors have disrupted schools and have even resulted in decreased attendance due to unfounded fears of violence. The issues of text messaging in particular, and cellphones in general, have been credited with sometimes creating more anxiety and panic than any actual threats or incidents that may have triggered the rumors.

While safety experts now recognize that mobile technology is here to stay, for many years some were of the opinion that allowing students to carry cellphones at school was driven more by parental and student convenience than safety.

An opinion that bears out in some research.

In 2010, when Pew Research Center interviewed parents and teens about the role of cell phones in their lives, many teens said it was their parents who initiated their acquisition of a phone.19 They added that their parents were reluctant to take away their phones as punishment because it would sever the connectivity parents have come to rely on.

“[My parents] always needed us, they always needed me to have it, more than I needed to have it. Like, my mom always needed to reach me, so she would never take away the phone as punishment, because it was more useful for me to have it than for her to take it away,” one teenage focus group participant said.

The Loss of Children’s Independent Mobility (Or the End of Kids Playing Outside)

As we have become a more technologically sophisticated society, another interesting trend has taken hold. That of the loss of children’s independent mobility. Children’s independent mobility can be defined as their freedom to travel and play outside the home without adult supervision.

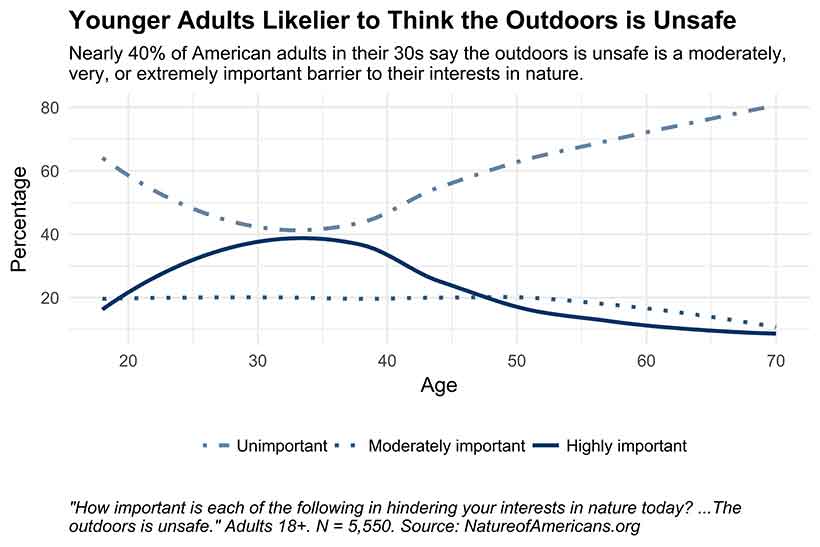

If that idea scares you a little, you’re not alone.

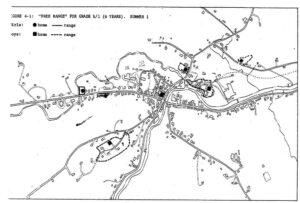

Environmental and developmental psychologist Roger Hart, who mapped how and where children spent their unsupervised time in one Vermont community in the mid-1970’s and again 35 and 40 years later, found a significant reduction in the children’s zones of play. Even though the community, according to Hart, has the same demographics and crime rate as it did in the 70’s.

Video: A trailer for the documentary created by filmmaker John Marshall and psychologist Roger Hart in the summer of 1975 as they recorded the outdoor play activities of the children in a small Vermont town. In this clip, children work with tools in the forest unsupervised by adults.

The loss of children’s independent mobility is concerning for a number of reasons.

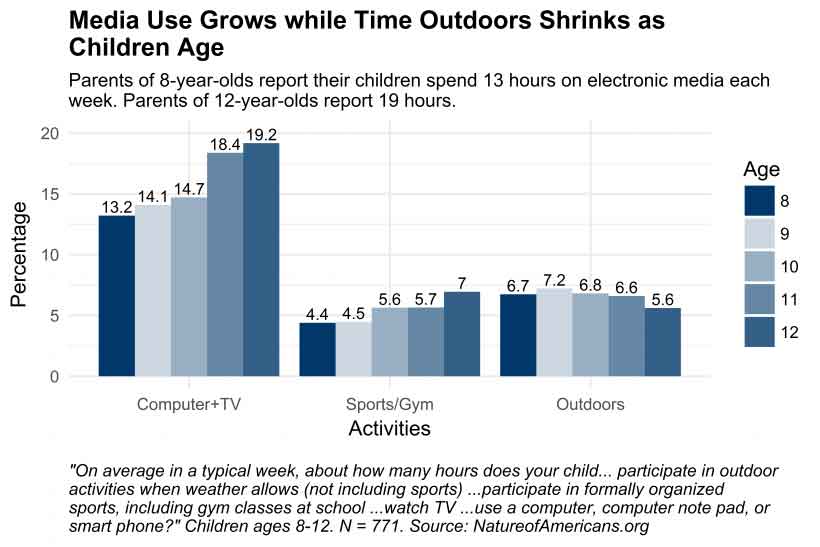

Children already spend more time on media and less time outside as they age.22 When parents require children to have adult supervision outside, their outdoor time diminishes even further.

But even if parents are available to spend hours with their kids playing outside, research shows that depriving kids of unsupervised time outside the home deprives them of their chance to have more social interactions with a wider range of people.23, 24 To develop more confidence.25, 26 And to cultivate better knowledge about their neighborhood and community.27

Studies have also shown that childhoods with greater autonomous mobility and more frequent opportunities for play in public places predict a stronger sense of community in adolescence.28 And that can have a positive effect on mental and emotional wellbeing, as well as provide a greater sense of purpose.

How Constant News is Making Parents Afraid to Let Their Kids Play Outside

Even before the internet, researchers established that media presentations of crime trends are generally unrelated to police statistics, and that public perceptions tend to resemble the media portrayal more closely than the statistics.29

They also established that violent crime predominates print and electronic news media.30

This hasn’t changed with the advent of the internet, but the amount of exposure we now have to coverage of traumatic events has escalated exponentially. And with it, anxiety and the belief that violent crime is on the rise when, in reality, the opposite is true.

Today we don’t even have to tune into the news to see it.

Smartphones and other digital devices are pre-programmed with news feeds on them. News headlines appear at the top of search engine results and social media is rife with links to sensational news stories either shared by friends or served up as paid content.

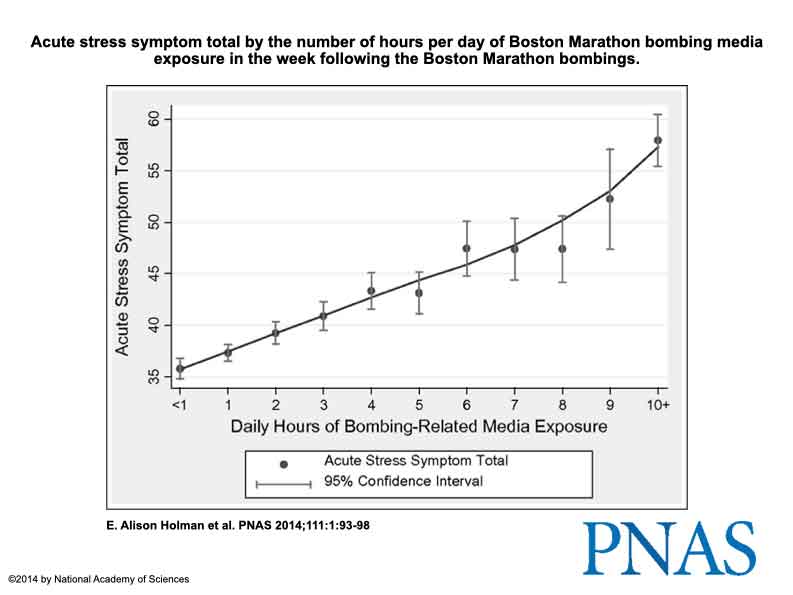

Researchers at the University of California, Irvine were in the unique position to survey a nationally representative group of over 4000 people before and after the Boston Marathon bombings of 2013.31 Later, they extended their study to include responses to the 2016 Pulse Nightclub mass shooting in Orlando, Florida.32

Learn How Persuasive Design Is Used to Create Habit Forming Digital Media

Everything You Need to Know

In a survey taken shortly after the Boston Marathon bombings, they found that repeated bombing-related media exposure of 6 hours a day or more was associated with greater likelihood of reporting high acute stress than was direct exposure to the bombings.

In a survey taken 6 months after the bombings, people who viewed 6 hours or more of news coverage of the bombings were more likely to exhibit symptoms of post-traumatic stress (PTS) than people who were at or near the bombings. Two years later, people who reported PTS at the 6-month mark were more likely to worry about future negative events which predicted increased media consumption and acute stress following the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando in 2016.

The findings reinforce earlier work that shows media coverage of collective traumas can trigger psychological distress in individuals far outside the directly affected community.33, 34

And they contradict the prevailing professional model that assumes people who were directly exposed to collective trauma are most at-risk for stress related disorders.

Researchers say their findings suggest that repeatedly engaging with trauma-related stories via the media may prolong the acute experience by constantly reminding people of trauma-related information and encouraging ruminative thinking. Especially in the early aftermath of the event when memory consolidation has been shown to be most pronounced.35 This timing of media coverage consumption may contribute to the abnormal consolidation of fear conditioning that has been associated in other studies with the development of acute and post-traumatic stress responses.

It also confirms previous research findings that suggest watching disturbing images may affect people’s ability to accurately appraise threat levels which may contribute to stress-related symptoms.36

Finally, researchers say that the results of the 3-year longitudinal study suggest that trauma-related media exposure perpetuates a cycle of high distress and media use.

How to Overcome Anxiety and Get Kids Playing Outside

Anxiety-inducing news stories are being fed to us constantly without our consent. To be as deliberate as possible about the news you consume, review the following checklist of automated news feeds that are most likely on your devices right now. Each item on the list links to instructions for how to turn it off. Consider disabling automatic news feeds from your device to see how you feel

- Disable automated news feeds from your smartphone or tablet.

Disable automated news feeds from your PC or Mac desktop or laptop

- Disable automated news feeds from your Google search results

To perform a Google search that doesn’t include the “Top Stories” section, use the “verbatim” tool. This works for mobile or desktop/laptop search. Click here to learn how to use the verbatim tool.

- Disable automated news feeds from your browser’s start page.

Google Chrome: Click here to learn how to disable “Discover” on Chrome. Scroll all the way down to the subheading “How to Enable or Disable Discover in Chrome” then the sub-sub-heading “To disable Discover in Chrome”.

Apple Safari: Click here to learn how to disable “Shared with You”. Apple recently introduced a feature called “Shared with You” that takes links people have sent you in Messages and makes them automatically available in other apps on your iPhone or Mac. Now when you open a new tab in Safari, you’ll see links to any news stories that were sent to you in Messages.

Click here to learn how to disable “Siri Suggestions” from the Safari start page on your Mac. Siri Suggestions will show you sites it thinks you might want to visit which often include news stories. Click here to learn how to disable “Siri Suggestions” from the Safari start page on your iPhone, or iPad.

Studies show that familiarity with a geographic area, as well as with the people who live and work there, is effective in combating fear of crime.37 We advise clients who are anxious about their kids’ safety to turn off their devices and get outside with their children to meet their neighbors as a family.

Many parents also fear judgment from others if they let their kids play outside unsupervised. We’ve all read news stories about parents having child protective services called on them for letting their kids walk to the park alone. Utah just passed a law to protect parents from having this happen.38

Early-childhood educator and developmental specialist Allana Robinson says, when neighbors don’t know each other, the only resource they feel they have when they see an unsupervised child is to call the police. That’s why Robinson says she went door-to-door in her neighborhood with her son to meet her neighbors and let them know they might see him playing outside without her.39 “I gave my phone number to everybody and said, ‘If you ever see him doing something questionable that you’re not sure is safe or appropriate, please send me a text message. I will deal with it,’” she told the hosts of podcast Balance365 Life.

When parents spend time outdoors, they become a model for kids of how to play outside. A national study of 771 US children and thousands of adults highlights this important role parents play.40 Children of parents who describe themselves as outdoor oriented spent more than twice as much time per week outside. Children also tended to care for the plants and animals that their parents provided. According to the study, adults often get hung up on the definition of “authentic” and “pure” nature, but for kids, the outdoors is anything outside their door. Kids describe special places outdoors and unforgettable memories in their backyards or nearby woods, creeks, and gardens.

Resources to Learn More

- Should The Parkland Shooting Change How We Think About Phones, Schools and Safety? [NPR]

- School shootings are extraordinarily rare. Why is fear of them driving policy? [Washington Post] – Article by David Ropeik, retired Harvard professor and risk communication consultant

- Anxiety Over School Shootings: Finding proactive ways to deal with worried feelings [Child Mind Institute]

- Helping Children Cope With Frightening News: What parents can do to aid scared kids in processing grief and fear in a healthy way [Child Mind Institute]

- The Overprotected Kid: A preoccupation with safety has stripped childhood of independence, risk taking, and discovery—without making it safer. A new kind of playground points to a better solution. [The Atlantic]

- Childhood revisited: Through longitudinal research, Roger Hart seeks to inform debate on the changing nature of childhood play. [APA]

- The Geography Of Childhood [This American Life]

- The Internet wants to keep you ‘doom-scrolling.’ Here’s how to break free. [Washington Post]

1. Over Four in Five Parents Cite Safety and Peace of Mind as the Top Reasons for Parents Allowing Children to Have Cell Phones.” (2010, August 17). Ipsos.Com. Retrieved November 17, 2021, from https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/over-four-five-parents-cite-safety-and-peace-mind-top-reasons-parents-allowing-children-have-cell

2. RLenhart, A., Ling, R., Campbell, S., & Purcell, K. (2010, April 20). Chapter Three: Attitudes towards cell phones. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2010/04/20/chapter-three-attitudes-towards-cell-phones/

3. McConomy, S. (2019, July 15). Kids Cell Phone Use Survey 2019 – Truth About Kids & Phones. SellCell.Com Blog. https://www.sellcell.com/blog/kids-cell-phone-use-survey-2019/

4. National School Safety and Security Services. (2019, February 20). Cell Phones and Text Messaging in Schools. Schoolsecurity.Org. https://www.schoolsecurity.org/trends/cell-phones-and-text-messaging-in-schools/

5. The 50th annual PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools: Teaching: Respect but dwindling appeal. (2018, September). PDK International. https://pdkpoll.org/

6. McConomy, S. (2019, July 15). Kids Cell Phone Use Survey 2019 – Truth About Kids & Phones. SellCell.Com Blog. https://www.sellcell.com/blog/kids-cell-phone-use-survey-2019/

7. Common Sense Media. (2019, October 28). The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens, 2019. Commonsensemedia.Org. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens-2019

8. Kaspersky. (2019, September 16). 84% of parents are worried about their child’s online safety, but aren’t taking the time to talk about it. Kaspersky.Com. https://www.kaspersky.com/about/press-releases/2019_parents-are-worried-about-their-childs-online-safety

9. Marvin, R. (2018, August 13). 76 Percent of Parents Concerned For Children’s Online Safety. PCMAG. https://www.pcmag.com/news/76-percent-of-parents-concerned-for-childrens-online-safety

10. Child Trends. (2019, November 19). Infant, Child, and Teen Mortality. https://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=infant-child-and-teen-mortality

11. Child Trends. (2019)

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2019 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2020. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html on Dec 16, 2021 1:11:34 PM

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2019 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2020. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html on Dec 16, 2021 1:11:34 PM

14. Nicodemo, A. (2020, April 23). Schools are safer than they were in the 90s, and school shootings are not more common than they used to be, researchers say. News @ Northeastern. https://news.northeastern.edu/2018/02/26/schools-are-still-one-of-the-safest-places-for-children-researcher-says/

15. James Alan Fox and Emma E. Fridel, “The Three R’s of School Shootings: Risk, Readiness, and Response,” in H. Shapiro, ed., The Wiley Handbook on Violence in Education: Forms, Factors, and Preventions, New York: Wiley/Blackwell Publishers, June 2018.

16. Fox, J. A. (2021, December 1). @jamesalanfox. Twitter. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://twitter.com/jamesalanfox/status/1466201049455370252

17. National School Safety and Security Services. (2019, February 20). Cell Phones and Text Messaging in Schools. schoolsecurity.org. https://www.schoolsecurity.org/trends/cell-phones-and-text-messaging-in-schools/

18. Trump, K. (2016, March 9). Study finds rapid escalation of violent school threats. School Security. https://www.schoolsecurity.org/2015/02/study-finds-rapid-escalation-violent-school-threats/

19. Lenhart, A., et. al. (2010, April 20). Chapter Three: Attitudes towards cell phones. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2010/04/20/chapter-three-attitudes-towards-cell-phones/

20. Invisibilia. (2015, January 16). Fearless. NPR. https://choice.npr.org/index.html?origin=https://www.npr.org/programs/invisibilia/377515477/fearless?showDate=2015-01-16

21. Policy Studies Institute. (2015, July). Children’s Independent Mobility: an international comparison and recommendations for action : WestminsterResearch. Westminsterresearch.Westminster.Ac.Uk/. https://westminsterresearch.westminster.ac.uk/item/98xyq/children-s-independent-mobility-an-international-comparison-and-recommendations-for-action

22. Kellert, S., Case, D., Escher, D., Witter, D., Mikels-Carrasco, J., & Seng, P. (2017, April). The Nature of Americans: Disconnection and Recommendations for Reconnection. Natureofamericans.Org. https://natureofamericans.org/

23. Tranter, P., & Whitelegg, J. (1994). Children’s travel behaviours in Canberra: car-dependent lifestyles in a low-density city. Journal of Transport Geography, 2(4), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/0966-6923(94)90050-7

24. Tranter, P., & Pawson, E. (2001). Children’s Access to Local Environments: A case-study of Christchurch, New Zealand. Local Environment, 6(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830120024233

25. Hillman, M. (1990). One false move: a study of children’s independent mobility. Policy Studies Institute XLV.

26. Joshi, M. S., Maclean, M., & Carter, W. (1999). Children’s journey to school: Spatial skills, knowledge and perceptions of the environment. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 17(1), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151099165195

27. Lee, J., & Abbott, R. (2009). Physical activity and rural young people’s sense of place. Children’s Geographies, 7(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280902798894

28. Qiu, L., & Zhu, X. (2021). Housing and Community Environments vs. Independent Mobility: Roles in Promoting Children’s Independent Travel and Unsupervised Outdoor Play. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 2132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042132

29. Sheley, J. F., & Ashkins, C. D. (1981). Crime, Crime News, and Crime Views. Public Opinion Quarterly, 45(4), 492. https://doi.org/10.1086/268683

30. Chermak, S. M. (1994). Body count news: How crime is presented in the news media. Justice Quarterly, 11(4), 561–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418829400092431

31. Holman, E. A., Garfin, D. R., & Silver, R. C. (2013). Media’s role in broadcasting acute stress following the Boston Marathon bombings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1316265110

32. Thompson, R. R., Jones, N. M., Holman, E. A., & Silver, R. C. (2019b). Media exposure to mass violence events can fuel a cycle of distress. Science Advances, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav3502

33. Vasterman, P., Yzermans, C. J., & Dirkzwager, A. J. E. (2005). The Role of the Media and Media Hypes in the Aftermath of Disasters. Epidemiologic Reviews, 27(1), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxi002

34. Wright, K. M., Ursano, R. J., Bartone, P. T., & Ingraham, L. H. (1990). The shared experience of catastrophe: An expanded classification of the disaster community. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 60(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079199

35. Parsons, R. G. (2013, January 28). Implications of memory modulation for post-traumatic stress and fear disorders. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/nn.3296?error=cookies_not_supported&code=6f0cab00-bcf8-4875-b196-60da025d3a9a

36. Marshall, R. D., Bryant, R. A., Amsel, L., Suh, E. J., Cook, J. M., & Neria, Y. (2007). The psychology of ongoing threat: Relative risk appraisal, the September 11 attacks, and terrorism-related fears. American Psychologist, 62(4), 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.62.4.304

37. Lorenc, T., Petticrew, M., Whitehead, M., Neary, D., Clayton, S., Wright, K., Thomson, H., Cummins, S., Sowden, A., & Renton, A. (2014). Crime, fear of crime and mental health: synthesis of theory and systematic reviews of interventions and qualitative evidence. Public Health Research, 2(2), 1–398. https://doi.org/10.3310/phr02020

38. de la Cruz, D. (2018, March 29). Utah Passes ‘Free-Range’ Parenting Law. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/29/well/family/utah-passes-free-range-parenting-law.html

39. Brees, A., Campbell, J., & Koski, L. (2019, June 5). Balance365 Life Radio: Episode 69: The Benefits Of Unsupervised Outdoor Play. Balance365 Life Radio. https://balance365liferadio.libsyn.com/69-the-benefits-of-unsupervised-outdoor-play

40. Kellert, S., Case, D., Escher, D., Witter, D., Mikels-Carrasco, J., & Seng, P. (2017, April). The Nature of Americans: Disconnection and Recommendations for Reconnection. Natureofamericans.Org. https://natureofamericans.org/

Need Help? Reach out.

and digital media overuse treatment and education.

Our experienced and knowledgeable therapists can help.