Therapist Training Series:

How the Internet Has Changed the Parent-Child Relationship

Tracy Markle, MA, LPC &

Dr. Brett Kennedy, Psy.D.

In This Article

Today’s parent-child relationship is one of 24-hour connectivity. Most parents cite peace of mind as the primary reason for giving their child a cellphone, but how do teens feel about this new digital contract? One in which they are only allowed to venture outside the home on their own if they promise to keep their phone on them at all times and immediately respond to any communication from their parents? Those of us who work with kids must develop an understanding of the pressures they face under this new kind of constant parental monitoring and surveillance. Especially as they reach adolescence. A time when developmental milestones of autonomy and independence are healthy. Therapists, educators, and others who work with youth should read on to learn how parental overreliance on cell phone technology could lead to less parent-child communication and even erode mutual trust.

The New Parent-Child Relationship: 24-Hour Connectivity

“In the digital era, for many teenagers, it appears that staying connected with their parents is a part of the exploration of public space and developing private relationships,” says a research article by French socio-anthropologist Jocelyn Lachance who interviews teenagers to learn how they feel about and navigate this dynamic.1

Not only does the modern family reinforce this information sharing amongst themselves, but the digital tools they use to stay connected also give corporations access to that information. Even as parents express concerns about their children’s privacy online.

So, this new parent-child contract also helps acculturate the child to another social norm of the digital age: that of sharing personal information or permitting surveillance in exchange for getting something of perceived value.2, 3

In the digital era, for many teenagers, it appears that staying connected with their parents is a part of the exploration of public space and developing private relationships.

Though parents often say they gave their child a phone for their own peace of mind, Lachance found this may not always be the result.4

Teenagers interviewed during his research said that their parents sometimes contact them, not because they have a reason to believe the teen is unsafe, but to be reassured of the digital connection and the teen’s compliance with the response-on-demand agreement.

Few teenagers avoid receiving texts or calls from their parents during the day, even in class.5 Much of these communications are to organize family logistics, but many parents also reach out for small talk, according to several of the teens interviewed. One 15-year-old told interviewers his parents call, “for everything and nothing.” While a 14-year-old girl said she thinks her parents need to be reassured, despite the presence of classmates and teachers. “It happened several times that they contacted me at noon to check that everything was fine,” she told interviewers.

According to the teens, in these instances, their parents aren’t asking, “how are you?”, “where are you?”, or “who are you with?” But rather, “are you still reachable?” and “will you answer me when I contact you?”

While the teenagers interviewed largely empathize with their parents’ need to know they are safe, some also harbor resentments about the frequency with which their parents contact them. Especially when they believe their parents know they are in a safe place under adult supervision.

“I know if I don’t call my parents I will have problems. So, I send a message or I call them. It is normal they worry about me, but when I am with a friend where her parents are there, nothing can happen to me. It’s not like if I’m going out in town at night. There’s no reason to worry, I think. But they want to know how I am and, in exchange, I have the right to go to my friend’s home. It’s a kind of deal,” one 15-year-old interview participant is quoted as saying in the article.

Without establishing clear reasons for checking in ahead of time, boundaries can become distorted and parents can engage in these “checking-in” behaviors instead of managing their own anxieties and determining whether there really is something to worry about.

Four different strategies for navigating this tension arose from the interviews with the teens.

- The majority of teens paid close attention to their phone at all times so they wouldn’t miss a contact from their parents. “For them, checking their cellphone regularly and keeping the alarms and notifications on are the most important. They will always answer quickly to avoid worrying their parents, and also to avoid problems with them as some teens had experienced before,” the article says.

- Another group routinely anticipated when their parents might want to hear from them and reached out first. The article says that these teens presume to understand their parents’ psychology and internalize it in such a way as to manage their time and activities to anticipate the moment their parents are expecting a signal from them. Lachance observes that texting helps resolve the tension between the parent’s desire to keep the bond alive and the teenager’s desire to conserve these moments of parental gaze. It’s a solution that satisfies everyone for now. (Because the contract can and will be adjusted as the teen grows and the parent feels more or less confidence and trust in them.) Parents obtain confirmation that the link can be reactivated, that their children are still within the security perimeter of the connection. And the teenagers fulfill their part of the contract without disrupting the course of their activities.

- A third group of teenagers sometimes ignored their parents’ attempts to contact them when they judged parental contact unnecessary, such as when they felt their parent had no reason to believe they were unsafe.

- A fourth group of teens created a situation where they were unable to connect with their parents, most commonly by allowing the battery on their phone to die. “Last week, my phone was dead. So no phone anymore! My father didn’t know where I was and he made a drama about it when I got home, but I was honest. My phone was just dead!” a 17-year-old interview participant is quoted as saying.

Lachance notes that the content of the communications between the teens and their parents was rarely mentioned by the teens interviewed. It’s the act of calling or texting itself that stands out in interviews as the most significant thing. In other words, because of the meaning applied to this interaction, the digital link is strongly tested by the parents and significantly accepted or rejected by the teens. The ones that accept the terms of the contract by keeping in touch with their parents at all times seem to do so out of respect as well as empathy. They want to provide their parents with a feeling of security. For those who ignore their parents’ messages or reject their calls, their choice seems to be motivated by a need for empowerment.

Data Collection as Parenting Tool

Teens and tweens are constantly creating traces of data about their behavior on their smartphones through text and images as well as through geolocation tagging when it’s employed. Now parents have the ability to use this data to monitor their kids’ behavior when they are out of their sight. How this is changing the parent-child relationship is another issue examined in Lachance’s research.7

More than half of the teens interviewed said that their parents sometimes examine the images on their smartphones to learn details about their recent activities.

Teens described situations where their parents simply ask questions when the teen shows them photos or videos they shot during the previous evening’s events. Others said their parents might ask if the teen wants to show them photos from their recent activities. In both of these types of scenarios, the photos are a tool that facilitates interactions between parents and teens.

But a third, common interaction described by teenagers is when parents require the teens to give them access to their devices and answer questions about the content of images stored there.

“The narrative is no longer a discourse based on the elements chosen by the teen but based on the elements that appear in the photo and chosen by the parents,” the article says.

Many teens interviewed also said their parents utilize their stored text messages and private conversations on social media to monitor their behavior. Questions about text-based communications are often similar to questions about photos, but with text, teens have less latitude with which to interpret the content for their parents.

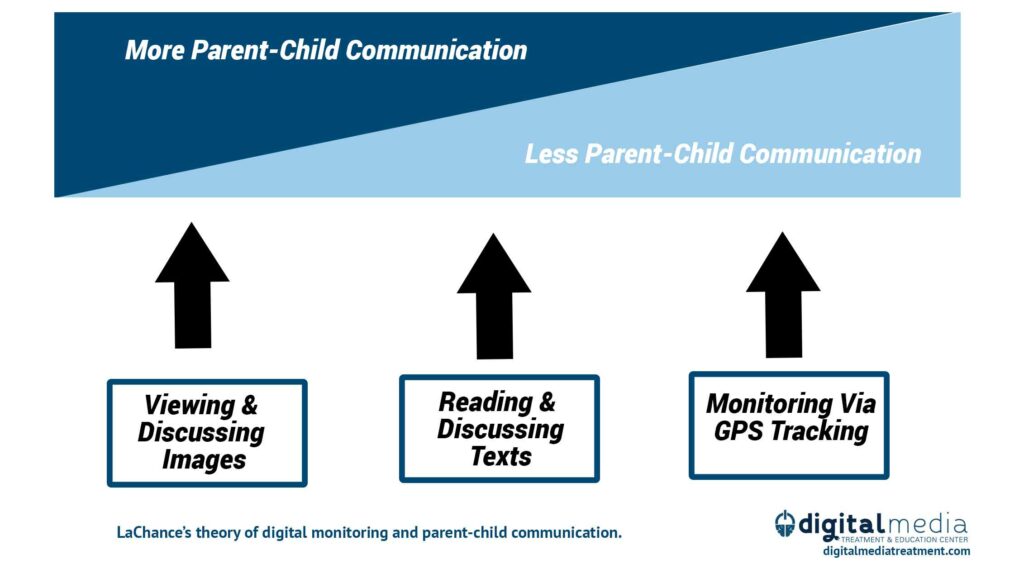

The article notes that the traces of data utilized by parents to monitor their children’s behavior—images, texts, and GPS tracking—exist on a spectrum of objectivity. The more objective the data, the less room the teenager has to create a narrative for their parents about their behavior. Of the three formats discussed in the article, GPS tracking is by far the most objective.

When parents employ GPS tracking on their teen’s device to monitor their activity, it removes any ability for the teen to interpret events during a confrontation. Instead, they are forced into silence.

Eight teens in the study reported discovering that their parents had tracked them through their phones. Notably, all eight of them confirmed their relationship with their parents was conflicted, sometimes even a few years after learning they were tracked.

In many of the interviews, teenagers told researchers that when they were confronted by their parents with data they deemed objective, they didn’t view arguing as an option. Even though they felt their parents’ surveillance of them was a breach of their rights and privacy.

The article concludes that when parents enhance their authority with the use of objective surveillance data such as geotagging, the parent-child exchange loses relevance or, “the objectivity of data replaces the subjectivity of words.”

The narrative of the confession is replaced by a feeling of deep regret amongst the teens, and at times a feeling of deep betrayal.

The study concludes that smartphones are providing a new form of control for parents over their children, one that prompted the teens to alter their behavior to navigate that of their parents. It also concludes that smartphones are providing a new form of data collection for parents about their children’s behavior. One in which children worry less about explaining their behavior and more about evading surveillance.

Family Data Collection and Parenting Style

Learn How Persuasive Design Is Used to Create Habit Forming Digital Media

Everything You Need to Know

The Digital Parent-Child Relationship: Monitoring Your Life 360

The connection between authoritarian parenting style and GPS tracking apps is most apparent when they are used to monitor a child at college.

On internet forums like Reddit and Quora it’s not hard to find posts from young adults asking for advice and support dealing with a parent who insists on tracking them on their smartphone. Often these parents have threatened to stop paying college tuition and living expenses if their adult child won’t keep a tracking app on their phone and continue to abide by their parents’ rules, even from a great distance.

Life360 is one of the most popular phone tracking apps used by parents to track teens and young adults. It has over 1.4 million downloads listed on the Google Play store at the time of this writing. Of course, 87% of US teens own an iPhone, and Apple doesn’t list download numbers on their App Store, but mobile app data aggregator SensorTower does.9 It says there were 1 million downloads of Life360 from the App Store in November of 2021 and it lists the app as #54 on the App Store’s top US grossing mobile apps.

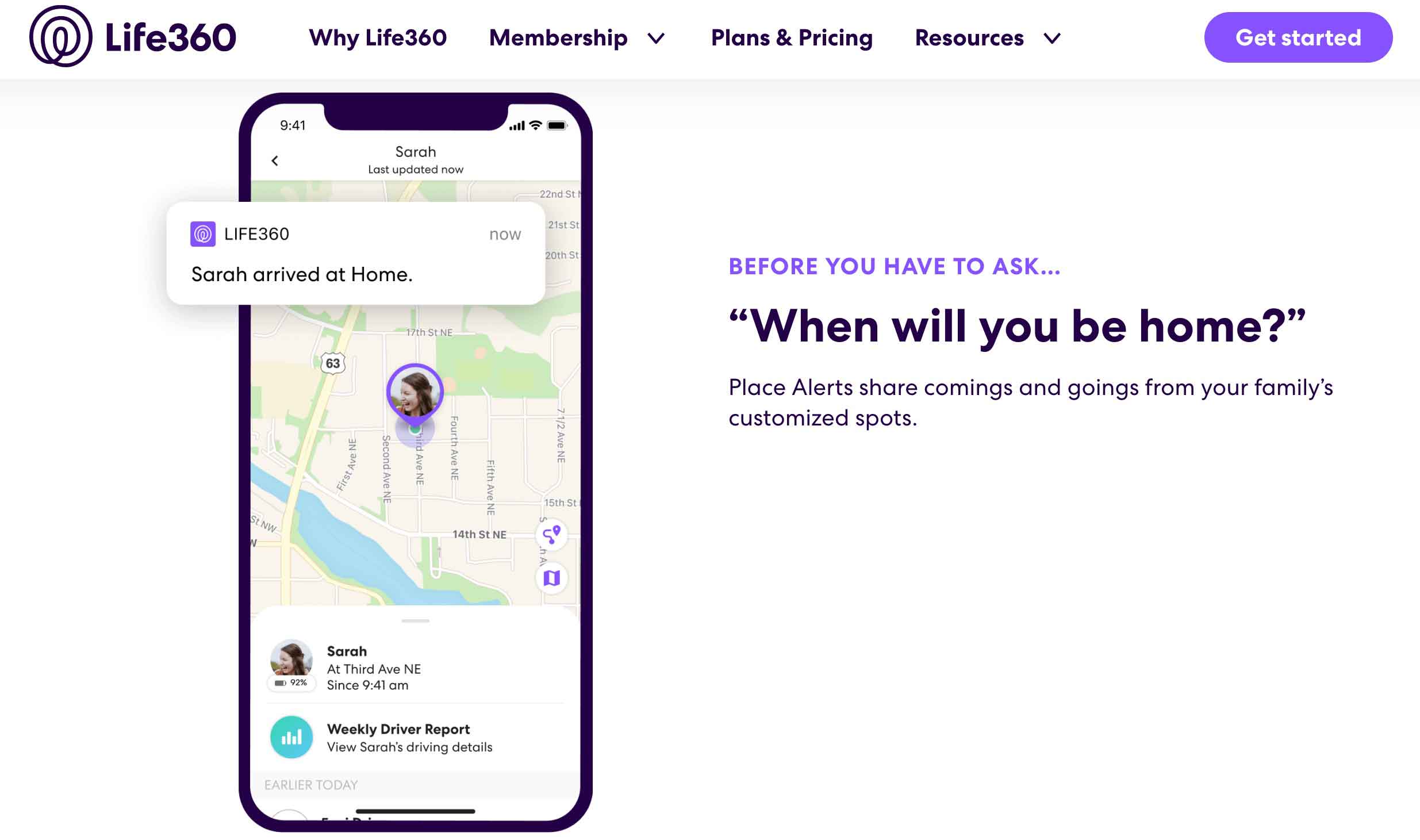

Life360 encourages families to create a “circle” on the app so that everyone in the family knows where everyone else is at all times. The faulty premise being that knowing your family member is in an expected location means they’re safe, and if they go to an unexpected location, they’re unsafe.

The app can track someone’s movements 24 hours a day and sends an alert if the person being tracked goes over the speed limit in their vehicle, uses their phone while driving, or leaves the perimeter of an area set for them by the person tracking them. It can even tell the user when someone in their circle needs to charge their phone battery and encourages the user to send the other person a message to do so.

Just as social media apps condition users to the dopamine reward they get from a notification about a like or comment, Life360 conditions users to the reward they get from a notification about the whereabouts of their child.

Video: A commercial for Life360—a geotracking app popular with parents who track their teenagers and college students—shows the constant notifications the app uses to draw users in. Notifications are key tools in persuasive design that help create habit-forming digital media.

In 2019, Life360 grew so popular with parents that videos about the app began trending among users on TikTok. Typing #life360 into the search field retrieves hundreds of videos. Some are instructional videos by young people teaching others how to hack the app to escape parental observation. Others use comedy to express their frustration with overbearing parents.

In the below TikTok video, for example, a college student imitates his father showing up to scold him because Life360 alerted him that his son was driving over the speed limit. He then imitates his mother calling him because she noticed on Life360 that he didn’t plug his phone in to charge it until very late the previous evening.

@garrettmccraw Who has to have Life360?😩 #fyp #foryou #life360 #parents #mom #dad #pov #funny #relatable

♬ original sound - Garrett

@life360ceo Asx:360 about to reach $1,000,000,000. I’ll put the money into making the app better for teens. The goal was safety not control. #life360 #banlife360

♬ оригинальный звук - Videographer | ROSTOV

Communications scholar Amy A. Hasinoff at the University of Colorado, Denver writes that apps like Life360 exemplify Silicon Valley’s success at selling products by framing them as addressing problems that have been overstated (such as the relative danger of going outside the home) with solutions that, in reality, can never be delivered (such as total safety).13

Life360 uses the tagline “Feel free, together”. An awkward premise implying one can be constantly monitored and free at the same time.

Gallery: Advertising materials from the Life360 website utilize the tagline “Feel free, together”, an awkward premise implying one can be constantly monitored and free at the same time. Life360 ads also promise to replace the need for parent-child communication with instant notifications about the comings and goings of everyone in the family.

Can Monitoring and Tracking Kids Be Done Respectfully?

There are children who view tracking apps as helpful tools for organizing the logistics of daily life with their parents. They often describe a mutual trust and respect between themselves and their parents typified by the fact that their parents aren’t overly reliant on technology to monitor their behavior. Instead, these parents make time to build closeness with their children through conversation.

At dTEC® we work with problematic digital media overuse and addiction. Engaging digital tools to manage that addiction may be necessary for some of our clients. However, we always advocate for a thoughtful approach that encourages parental communication and curiosity that enhances the parent-child relationship.

For most of the population, the decision to use digital parenting tools should be a reflection of the family’s values, and the result of a family discussion about the rationale and need to introduce this kind of oversight into the family. Not simply something that’s implemented for control.

This means maintaining transparency along with clear parameters and expectations around how that tech-based oversight will be used.

In this way, setting limits and providing oversight of children and teens can still support their autonomy and independence, as long as they understand the parameters vs. feeling betrayed or spied on.

But even in the happiest relationship, it’s important for parents to consider whether the convenience of using a tracking app to organize daily logistics is worth the amount of personal information about the family that must be shared with the corporations behind the apps in order for them to work. A recent investigation by news site The Markup found that Life360 “is selling data on kids’ and families’ whereabouts to approximately a dozen data brokers who have sold data to virtually anyone who wants to buy it.” 14

Resources to Learn More

- Phones Buzz in Class—With Texts From Mom and Dad [Wall Street Journal] (login required)

- Parents are texting their kids in class so much that schools are banning phones [Care]

(Summarizes above WSJ article) - Who’s That Texting Your Kids in Class 66% of the Time? Parents [FastCompany]

- Want to help your kids do well at school? Stop Texting Them! [Medium] — Article by a teacher

- ‘Don’t leave campus’: Parents are now using tracking apps to watch their kids at college [Washington Post]

- The Popular Family Safety App Life360 Is Selling Precise Location Data on Its Tens of Millions of Users [The Markup] Non-profit news site that investigates how powerful institutions are using technology to change our society.

- The domestic panopticon: location tracking in families [ACM Digital Library] — Qualitative study establishing that tracking software affords a means of digital nurturing but has the potential to undermine trust and serve as a detriment to nurturing.

- You Can Track Almost Everything Your Kids Do Online. Here’s Why That May Not Be a Good Idea [Time] — Article by psychologist and author Lisa Damour

- The Impact of Location-Tracking Apps on Relationships [Psychology Today]

- Your Parents are Watching: Digital Peace or Prison? [The Mirror] — Opinion piece from the award-winning, student-run news site at Van Nuys High School in Los Angeles, California.

- #Life360 hashtag feed [TikTok] — Teens and young adults post videos about their parents using one of the most popular child monitoring apps, Life360.

- I am Life360’s (misunderstood) cofounder and CEO – AMA [Reddit] — Q&A with Chris Hulls, CEO of Life360, held after hundreds of teens and young adults mobilized online to publicize their belief that Life360 enables their controlling parents.

- My parents want to keep tracking my location, and get worried if I am out late with friends. I am 24, live 500 miles away, and pay for my own bills. How do I tell my parents they’re being too much? [Quora]

- What does the panopticon mean in the age of digital surveillance? [The Guardian] A reexamination of the panopticon theory for the digital age.

- Black Mirror “Arkangel” asks “What is privacy under the threat of loss?” [Purple Car] A blogger and mother examines one episode of the tech dystopia series “Black Mirror” in which a child is implanted with a chip that allows her mother to see everything she sees.

4. Over Four in Five Parents Cite Safety and Peace of Mind as the Top Reasons for Parents Allowing Children to Have Cell Phones. (2010, August 17). Ipsos.Com. Retrieved November 17, 2021, from https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/over-four-five-parents-cite-safety-and-peace-mind-top-reasons-parents-allowing-children-have-cell

5. Lachance, J. (2019b). La famille connectée: de la surveillance parentale à la déconnexion des enfants [The connected family: from parental supervision to disconnecting children] (eden-1639-125596-35314 ed.). ERES, 78. https://www.amazon.com/famille-connect%C3%A9e-L%C3%A9cole-parents-French-ebook/dp/B07YVB3X23/ref=sr_1_2?keywords=jocelyn+lachance&qid=1637185998&sr=8-2

12. Wall Street Journal. (2020, August 23). How One CEO Dealt With the TikTok Taunts of Gen Z: He Hired Them (Comment). WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-one-ceo-dealt-with-the-tiktok-taunts-of-gen-z-he-hired-them-11598205883?commentId=84b6bc7e-eb8d-4624-98c7-39079431276b

13. Hasinoff, A. A. (2016). Where Are You? Location Tracking and the Promise of Child Safety. Television & New Media, 18(6), 496–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476416680450

Need Help? Reach out.

and digital media overuse treatment and education.

Our experienced and knowledgeable therapists can help.