How do social media and gaming affect athletes’ performance?

Tracy Markle, MA, LPC &

Dr. Brett Kennedy, Psy.D.

In This Article

Social media and gaming affect athletes’ performance in many undesirable ways. From the professional level down, coaches report that today’s athletes have a hard time focusing and experience increased challenges with communication skills necessary for successful training. In studies, college athletes report losing sleep because of their phones and researchers find that when athletes use social media and video games before and during competitions it leads to impaired performance. Coaches, therapists, and related professionals, read on to learn how too much social media and gaming can hurt athletes.

What Are Digital Media Overuse and Addiction?

The use of digital media, like video games, mobile apps, or websites, occurs on a spectrum. Healthy digital media use is on one end of the spectrum and addictive digital media use is on the other. In the middle is digital media overuse (DMO) and that’s where the majority of users fall. This is why we focus much of the articles on this blog on DMO. While digital media overuse isn’t addiction, it comes with its own set of health problems which we’ll discuss later in this article.

Digital media addiction, also called internet addiction or online addiction, is an umbrella term that can refer to an addiction to online video games, social media, online spending, surfing the internet (known as information overload), or online pornography. Only a small percentage of the overall population meets criteria for online addiction, but the most vulnerable group are college students followed by teenagers. This includes 8.5% of US children ages 8-18 and 13%-18% of US college students.1, 2

In 2018, WHO added gaming disorder to the category of behavioral disorder in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11), which went into effect in 2022. The 5th edition of the American Psychiatry Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) also named internet gaming disorder as a condition for further study.

WHO advises people who partake in gaming to be alert to the amount of time they spend on gaming activities, particularly when it’s to the exclusion of other daily activities or leads to changes in their physical or psychological health and social functioning. We further extend this advice to include any digital media use that is becoming overuse.

WHO also created a new category of impulse control disorder called Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD) which can include problematic pornography use. You may have heard it referred to as pornography addiction.

Diagnostic criteria in the ICD-11, for internet-based behavior and impulse disorders include a persistent pattern of failure to control the behavior or impulse to the point that the individual is neglectful of health and personal care or other interests, activities, and responsibilities. The behavior must persist for at least 6 months and sometimes up to twelve months, despite numerous efforts to significantly reduce it and despite adverse consequences or deriving little or no satisfaction from it. You can read about internet addiction criteria in more detail here.

Why Are Athletes Vulnerable to Digital Media Overuse and Addiction?

A core set of mental health diagnoses are often found to coexist with digital media overuse and addiction. Among them, at least three are commonly found in elite athletes. Those are depression, anxiety, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Depression & Anxiety in Athletes

Studies have found that mental health disorders are common among elite athletes and that elite athletes are at elevated risk for mental health issues such as depression and anxiety.3,4

Why are athletes more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety? Elite athletes are under a unique set of pressures imposed on them by family, community, and themselves.

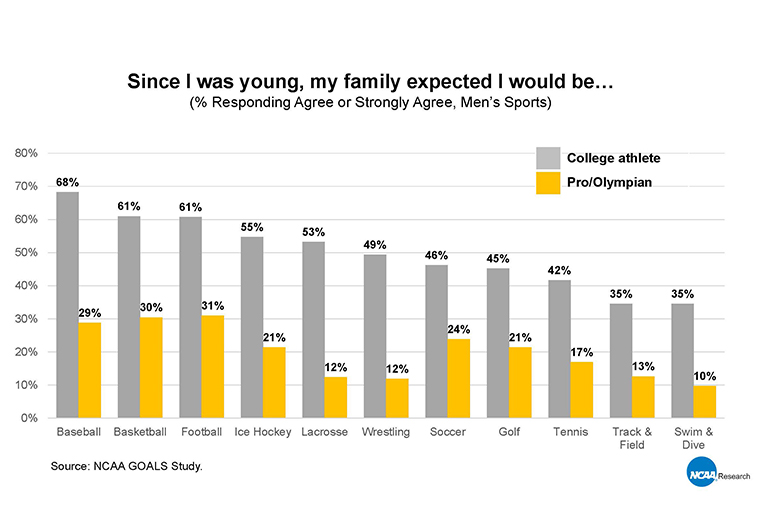

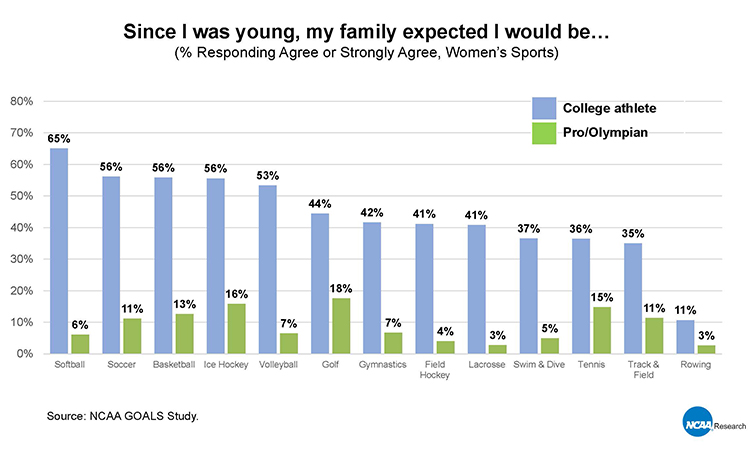

Familial Pressure

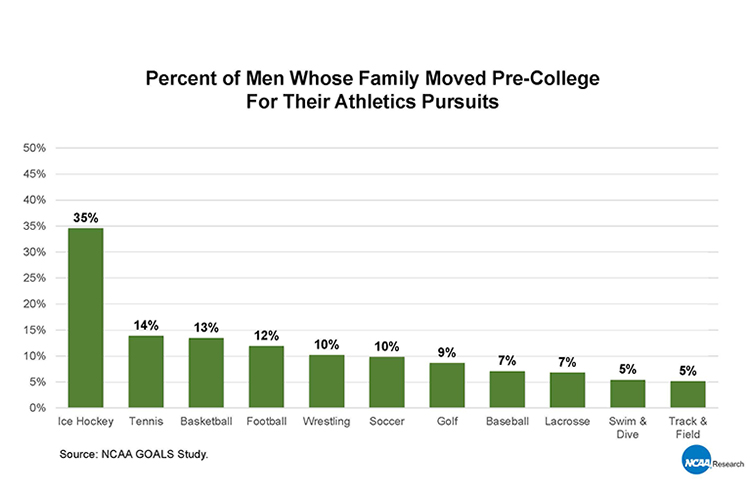

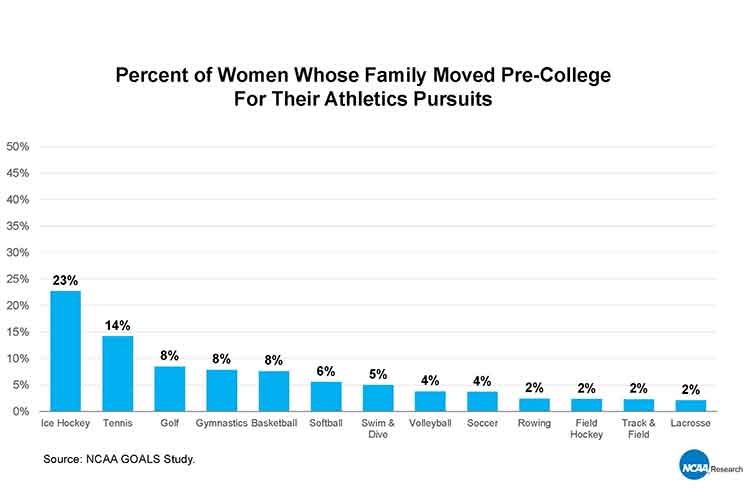

A 2019 survey of student athletes by The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) found that up to 68% of male student athletes and up to 65% of female student athletes were expected from a young age to be college-level players by their families.5 Up to 35% of male student athletes and up to 23% of female student athletes also reported their family had moved pre-college in order to further their athletic pursuits.

Self-Imposed Pressure

Up to 50% of male student athletes and up to 28% of female student athletes in the 2019 NCAA survey believed it was at least “somewhat likely” they would play professional or Olympic-level sports. When focusing only on Division 1 schools, that number increases to a staggering 76% of male student athletes in some sports and 47% of female student athletes in some sports who marked this statement as true.

Recruitment Pressure

Up to 88% of the student athletes in the 2019 NCAA survey chose their college because of athletics, but up to 46% say their role on the team has not turned out as it was described during recruitment.

Athletic Pressure

Division I student athletes in the 2019 NCAA survey reported a meantime of 33 hours a week spent on athletics. Which means that some student athletes are working the equivalent of a full-time job in addition to going to college. Division 1 baseball players, for example, reported a median 42 hours a week of time spent on athletics during baseball season. For women, Division 1 softball players reported a mean of 38 hours a week during softball season.

Academic Pressure

The student athletes in the 2019 NCAA survey reported an average of 37 hours a week spent on academics. Which amounts, essentially, to two full-time jobs between academics and athletics.

Sleep Deprivation

As you might imagine, this kind of schedule means student athletes are not getting a full night’s sleep. Survey participants reported an average of 6 hours and 15 minutes of sleep on a typical in-season weeknight. Football players reported the lowest average nightly sleep time of 5.85 hours while Ice Hockey players reported the highest average nightly sleep time of 6.95 hours.

With all of these factors in place, it’s not surprising that many student athletes in the 2019 NCAA survey reported arriving to college already feeling overwhelmed by all they have to do. The report’s authors note that this was especially true for female athletes. “Nearly 30% of female student-athletes compared to one-quarter of male student-athletes have felt difficulties piling up so high that they could not overcome them in the month prior to taking the survey,” the report says.

The NCAA also reports that “high percentages of study participants expressed a desire to have more time for socialization and relaxation,” without giving the exact percentages.6 “This was especially true among those student-athletes with high levels of academic and athletic time commitments (e.g., women, Division I student athletes). The median self-reported weekly time spent socializing/relaxing during the athletic season was 15.5 hours in 2019, down from 17.1 hours in 2015 and 19.5 hours in 2010,” the report says.

ADHD in Athletes

ADHD is either as common or more common among elite athletes than the general population. A recent global systematic review and meta-analysis found that the prevalence of persistent adult ADHD (after childhood diagnosis) in the general population was 2.58% and that of symptomatic adult ADHD (regardless of age at diagnosis) was 6.76%.7 While a review of 17 studies on student and elite athletes found the prevalence of ADHD in athletes ages 15 to 19 varied between 4.2% and 8.1%.8

Further, a narrative review in the British Journal of Sports Medicine notes that Major League Baseball (MLB), in the US, annually publishes the number of players who receive a Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE) which allows players to take certain drugs normally banned by the league. This includes stimulants prescribed for ADHD.9 For the 2017–2018 off-season to the end of the 2018 season, 101 players (approximately 8.4%) were granted TUEs for ADHD.

The review’s authors note that this is an under representative number because a) the MLB’s requirements for a TUE exceed the clinical standards required to establish a diagnosis in the community. As a result, there are athletes who have been diagnosed and prescribed stimulants in the community who do not meet the standards of the MLB policy, and thus would be excluded from the total numbers. And b) there are athletes who have been diagnosed with ADHD, but have been treated with a non-stimulant medication or no medication, and thus would not be reported to the MLB for inclusion in the report. The review’s authors also note that the MLB is the only professional sports league in the US that produces such a report on therapeutic drug exemptions for their players.

Athletes That Can't Separate from Their Phones

Anecdotally, athletes report and are observed using their phones at practice and competitions.10,11 Some coaches and other experts have spoken out about the negative effect they believe this has on athletic performance.12,13 The US news media has also picked up on the trend within the National Basketball Association (NBA).14, 15, 16 As a result, a few academic studies have attempted to understand the amount of time elite athletes spend on their phones.

A 2018 study of varsity athletes at two Canadian universities found that participants used their phones for an average of 32 hours per week.17 According to the study’s authors, athletes’ most used applications were social media which exceeded the use of any other application by 7 hours on average. Many athletes in the study reported anxiety, both when their phones are with them, and when they are separated from their phones.

A study conducted the same year with 199 athletes at Northern Michigan University found that the average number of hours the athletes spent on their smartphones each day was 5.2.18 And that the younger the student athlete, the more likely they were to stay up later on their phone. When ranking what their smartphones were used for, the student athletes ranked social media first, texting or messaging second, phone calls third, emailing fourth, school or work-related tasks sixth, athletic-performance-related (i.e. watching film, technique improvement articles) seventh, games, health-related apps, and news all tied for eighth, fantasy sports ranked tenth, and gambling eleventh. (The author notes that, because of the way usage was measured and certain three-way ties, there were no uses ranked in fifth or ninth place.)

While the study also found that the athletes’ perceptions of total smartphone use had a moderate relationship with objective measurements, there was a lack of accurate perception in regards to the number of times they checked their smartphones in a day.

Another study in 2016 of 298 adult athletes of varying levels from 13 countries and 30 different sports found that 31.9% used Facebook during a game or competition and 68.1% used Facebook within 2 hours before a game or competition.19 Researchers note that the athletes’ Facebook use after competition mirrored their Facebook use prior to competition with nearly three-quarters (71.9%; n = 214) of athletes accessing Facebook within 2 hours of the competition finishing.

Finally, a study examining the perceptions of 12 highly experienced US Tennis Association Player Development coaches and sport providers working with junior elite players reported that several coaches saw the Gen Z (defined in this study as athletes born after 1996) preoccupation with cell phone usage and social media as a major barrier to effectively coaching this generation.20 “These coaches saw cell phone usage as distracting, disengaging, and a time-wasting habit that took their focus away from their tennis development,” the study says.

Additionally, coaches in this study overwhelmingly characterized their Gen Z athletes with having difficulty paying attention and focusing over long periods. They also cited listening as a challenge for Gen Z athletes in their training. And they believed that players had difficulty expressing their emotions, were shy and hesitant to speak up, and lacked basic conversational skills (i.e., eye contact). They also perceived Gen Z athletes as preferring impersonal communication methods such as texting rather than face-to-face conversations or phone calls. And they believed that Gen Z athletes were more open via text.

How Does Social Media Affect Athletic Performance?

In studies, athletes report social media use as their primary smartphone activity. As mentioned earlier, one study found athletes’ weekly social media use exceeded the use of all other applications by 7 hours on average. A few studies have explored whether social media use might affect athletic performance.

Late-Night Tweeting Correlated with Reduced Athletic Performance

A review of NBA game statistics between 2009 and 2016 for 112 verified Twitter-using NBA players found that those who engaged in posting on Twitter or “tweeting” late at night scored fewer points and achieved fewer rebounds during their games the next day.21 To perform this study, researchers compared the time stamps on the verified, public Twitter accounts of NBA players with their in-game statistics on Yahoo! Sports.

“Late-night tweeting (compared to not late-night tweeting) is associated with within-person reductions in next-day game performance,” the report says. Since players who engaged in late-night tweeting played less time per game, researchers decided not to include number of turnovers and personal fouls, as those were likewise diminished. Instead, they report, “the critical measure of shooting accuracy – which is not time dependent – provides the clearest evidence of a performance penalty following late-night tweeting activity (between 11:00 pm and 7:00 am); players successfully make shots at a rate 1.7 percentage points less following late-night tweeting.” Late-night tweeting was also associated with approximately 1.1 fewer points scored and 0.5 fewer rebounds in the next day’s game.22

The study’s authors say these results suggest acute sleep deprivation, as measured via late-night Twitter activity, is associated with changes in next-day game performance among professional NBA athletes. And more broadly, that the use of late-night social media activity may serve as a useful general proxy for sleep deprivation in other social, occupational, and physical performance-based contexts.

Facebook Use Correlated with Sport Anxiety

The 2012 Summer Olympics in London were the first to feature athletes assimilated to an established social media culture. For example, in an article published less than a month before the games, the training regimen of Australian swimmer and three-time Olympic gold medalist Stephanie Rice revealed an elite athlete disciplined in all ways but one.23

“With her focus on winning gold at the Olympics, Rice’s social life is low-key. Most nights she is in bed by 10pm, distracted only by social media —replying to Twitter messages or checking Facebook,” the report said.

Incidentally, Rice placed fourth in London in one of the events for which she broke the world record and won gold in Beijing in 2008. She also tied for sixth in London in another of the events for which she broke the world record and won gold in Beijing. Obviously none of that can be directly tied to her newfound social media habit but being embroiled in a Twitter scandal during the weeks leading up to the games in London couldn’t have helped.24

Rice’s teammate Emily Seebohm was also a favorite to win the gold in her event, the women’s 100-meter backstroke. But she lost by a fraction of a second to American swimmer, Missy Franklin. Afterwards, Seebohm told journalists that staying up late using social media such as Facebook and Twitter may have contributed to her loss.25

“I don’t know, I just felt like I didn’t really get off social media and get into my own head,” Seebohm told reporters.

“I obviously need to sign out of Twitter and log out of Facebook a lot sooner than I did,” she said.26

Twelve hours later, after much public shaming on social media and the news, she recanted her comments and placed the blame on anxiety.27

“I don’t think Twitter and Facebook cost me a gold medal,” she said.

“I think me, myself, cost me the gold medal. I think I was just too nervous for my own good and that just cost me.”

In other interviews, Seebohm told reporters that she was so nervous, she was hardly able to eat the day of the race.28

Her coach Matt Brown also told reporters that social media overload was an issue for his swimmers.

“I’d love to throw some of those phones away,” he said.

Inspired by events like these, and building upon previous studies that found a correlation between social anxiety and Facebook use, researchers in Australia sought to learn whether Facebook use might correlate with sport anxiety.

Sport anxiety, (or sport-related anxiety), is a known sub-category of social anxiety that can affect athletic performance.29 Emerging research now suggests that sport anxiety might also play a role in sport injury prevention, occurrence, rehabilitation, and timing of an athlete’s return to sport activity.

To explore any possible links between Facebook use and sport anxiety, researchers recruited 298 male and female adult athletes from 13 different countries, representing six different ethnicities and 30 different sports. Participants completed the Sport Anxiety Scale-2 (SAS-2) and a questionnaire about their Facebook use.30 The results showed that nearly one-third checked Facebook during competition and more than two-thirds checked Facebook at least 2 hours prior to competition.

“This result should be concerning for coaches and sport psychologists because Facebook could act as a distraction from optimal psychological preparation and concentration on the task during the game,” the report says.31

Researchers found that Facebook use within 2 hours prior to competition was significantly and positively correlated with the concentration disruption component of sport anxiety. “The length of time before a sport competition that Facebook was accessed was related to concentration disruption reported, with the closer to the beginning of the competition an athlete accessed Facebook, the more concentration disruption they may experience,” the study says.

Regression analyses also revealed that having push notifications enabled on athletes’ phones predicted 4.4% of the variability in sport anxiety.

“Push notifications being enabled were significantly associated with SAS-2 concentration disruption, SAS-2 worry and SAS-2 sum, predicting 4.4% of the variability in sport anxiety. Additionally, Facebook use before a competition was significantly associated with SAS-2 concentration disruption and SAS-2 worry was significantly associated with Facebook friends,” the report says.

The study’s authors caution interpreting the direction of the relationship between sport anxiety and Facebook use because if higher levels of concentration disruption are reported before a competition, these athletes may use Facebook to distract themselves.

Social Media and Gaming Affect Athletes' Performance through Mental Fatigue

Multiple studies have shown that mental fatigue impairs athletic performance.32 More recently, researchers have explored how social media and video game use might play into this dynamic.

A study published in 2019 of 20 professional male soccer players found that 30 minutes or more of using WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram on a smartphone caused mental fatigue and impaired passing decision-making.33

A 2020 study of 25 professional male soccer players identified a group effect of impairment on passing decision-making performance when players either used a social networking smartphone app for 30 minutes or played a video game for 30 minutes.34

To conduct the study, researchers had athletes engage in one of three activities before playing a match against other participants in the study. For the experimental conditions, athletes used Facebook and Instagram on a smartphone for 30 minutes or they played the video game FIFA 18 for 30 minutes. As a control, participants watched a 30-minute video of advertisements. A short (less than 3-minute) Stroop Task was administered to measure fatigue among the athletes before and after their 30-minute experimental or control activity. Results showed social media and video game use induced mental fatigue among the athletes compared with those who watched a video.

Participants played soccer matches ten minutes later. The matches were videotaped and reviewed by two experienced researchers who analyzed and categorized each of the athletes’ passing decisions as appropriate or inappropriate. (They were blinded to which experimental treatment each athlete had undergone prior to the match in order to decrease bias.) Athletes who used social media or played FIFA 18 made as many passes as those who watched a 30-minute video. However, those passes were rated far lower in quality than those of the control group.

The results showed significant difference in accuracy and response time following induced mental fatigue in those athletes who used social media applications and video games compared with those who watched a 30-minute video.

The study’s authors conclude that the use of social networks and playing video games before a soccer match compromises the passing decision-making performance of athletes. Further, they say coaches should be aware of these impairments and avoid excessive use of them (i.e. 30min) before matches.

A 2021 study of 21 elite amateur boxers (eight female and 13 male; 7 amateurs of national level and 13 amateurs of regional level; with a standard mean age of 23.33 ± 3.46 years), found that both attack and defense decision-making performance were impaired after subjects used social media applications on a smartphone for 30 minutes and after they played video games for 30 minutes.35

Finally, a 2020 study that came too late for the 2012 Australian swim team found that using social media on a smartphone for 30 minutes was associated with slower race times for high-level swimmers.36

Researchers studied 25 international-level swimmers (14 male, 9 female; mean age of 20.4 years). Each athlete participated in three freestyle races— 50-meter, 100-meter, and 200-meter—under two conditions: after 30 minutes of social media smartphone app use and after watching 30 minutes of a coaching video on an 84-inch screen.

As with the soccer players and boxers in the other studies, researchers found that 30 minutes of social media use on a smartphone increased both the swimmers’ perceived mental fatigue and their response time on a Stroop test compared with watching a 30-minute video.

When subjects were fatigued by social media use, they showed a marked decline in performance during freestyle races after 50 meters.

A significant condition-time interaction for the swimmers’ 100-meter freestyle performance was observed with a significantly slower performance following smartphone app use evident in the last half of this race, but not in the first half,” the report says. “We also found a condition-time interaction in the same direction, (slower for swimmers who used the smartphone app) for the 200-m freestyle performance, with the slower performance occurring in the second but not the first, third, or fourth quarters of this race.”

Thus, the main findings showed that mental fatigue impaired performance in 100-meter and 200-meter freestyle without changing the pacing.

“The percentage differences between experimental conditions (mental fatigue vs. control) was approximately 2.0%. In professional athletes, this small percentage represents the difference between the winner and fourth place. For example, in the 2019 World Championship, the time difference between the winner (Dressel) and fourth place (Chiereghini) in the 100-m freestyle race was 0.92 seconds, 1.95% difference (FINA, 2019),” the report says.

Athletes and Gaming Disorder

Video: Minnesota Timberwolves center Karl-Anthony Towns confesses he played Fortnite with teammate Andrew Wiggins until 6 AM while on the road for a game against the Indiana Pacers.

The National Hockey League (NHL) is now reportedly asking all potential recruits whether they’re addicted to Fortnite.43 Multiple Major League Baseball teams, as well as Vancouver’s NHL team, have also created rules around gaming in an attempt to keep their players focused on the task at hand.44,45

One sports psychologist who works with professional soccer clubs in the UK told Reuters that gaming disorder is soccer’s hidden “epidemic”.46 Adding that the number of soccer players seeking treatment from him for gaming addiction tripled after COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020.

Despite this abundance of anecdotal evidence, the prevalence of gaming disorder among elite athletes is all but unstudied by clinical researchers.

We found just one study that sought to determine whether problem gaming, (which the researchers clarify is not the same thing as gaming disorder), is more prevalent among elite athletes.47 After surveying 352 college-level athletes, the researchers concluded that problem gaming is as prevalent as it is in the general population. However they did find the prevalence of problem gambling among their subjects to be on the high end of the prevalence rate in the general population. And a significant positive correlation between problem gambling and problem gaming was observed. The researchers also noted a marked gender disparity in the rate of prevalence. Lifetime prevalence of problem gaming in the college athletes studied was 2% (4% in males and 1% in females, p = 0.06), the report says.

Given that sports organizations are eager to get a handle on their players’ growing distraction with online gaming, one group of researchers set out to better understand it. They conducted semi-structured interviews with 22, Division-1, male, college athletes about their usage of and motivations for playing Fortnite.48 Based on the comments of the participants, they identified six usage and motivational themes:

- Fortnite as a Competitive Outlet

- Fortnite and Addiction

- Fortnite as Shared Athletic Experience

- Fortnite as Social Bonding

- Fortnite and External Social Connections

- Fortnite as Relaxation

Of the six, the theme of addiction was mentioned most and by the most participants. Twenty of the 22 athletes made a combined 78 addiction-related comments. The next most common theme was social bonding. Nineteen of the athletes made 72 social bonding-related comments. The other four categories received far less, but nonetheless significant numbers of comments.

The following are selected comments from the two most mentioned motivations, Addiction and Social Bonding.

On Fortnite and Addiction:

“I had to put a lot of stuff on the back burner for Fortnite. School, homework, practice, my sleep, my body. I was ready to skip treatment a couple of times. Tutoring-I’m not trying to go to tutoring. I go to tutoring for 30 minutes, then run up out of there to run back to get on Fortnite. It takes time. It takes time away from the things that you really need.”

“I probably spent about six hundred, seven hundred dollars on Fortnite. I still buy skins to this day, I know it doesn’t make you play better or nothing. It’s just whenever you’re playing against somebody and they see you have a new skin, it’s like ‘Oh, he’s got that skin!’”

“If I got an hour break, I go home and try to play for forty-five minutes. Like last night I go until three in the morning. I started playing at 10:00 play like all day until like all night. I didn’t go to sleep until three in the morning. I’ve already played today. I woke up this morning and I played. I’m gonna go home right now. I’ll play until I go to dinner, which is mandatory. And then I’m going to fix up my apartment a little bit more, and then play again until I go to sleep.”

On Social Bonding through Fortnite

“There’s not one [sport] team out there who doesn’t bond in one way, shape, or form, over Fortnite. You know, whether it’s goofy celebrations, whether it’s lingo from Fortnite that has just taken over like talk on the bus. People almost talk in a code where if you didn’t understand Fortnite you would not be able to put together ‘what on Earth is he talking about?’”

“Yeah, it’s definitely brought me closer to people I probably wouldn’t be as close with. I live in a house with [number] other guys and I’m pretty close with them but I feel like Fortnite’s brought me closer to the other people who I play Fortnite with.”

Resources to Learn More

- Managing Students-Athletes’ Motivations For Playing Fortnite [Athletic Director U]

- The good and bad of Twitter and college athletes [USAToday]

- How You Can Help Your Student-Athletes Cope with Negative Social Media [Athletic Director U]

- How Dopamine Causes Leaderboarding, Glues You To Your Phone, & Impacts Mental Health w/ Dr. Anna Lembke [Limitless Athlete Podcast]

- What to Know When Providing Therapy for Elite Athletes [The Modern Therapist’s Survival Guide Podcast]

- Gaming: a modern addiction [Rugby World]

- How Phones Distract Athletes from Coaches and Teammates [Next College Student Athlete]

- This College Basketball Team Banned Smartphones. Now it’s in the Final Four [Time]

- Twitter leads to under-performance on field of play, says Lord Coe [The Telegraph] (Requires free account creation)

- Quinn Pitcock’s video game addiction masked deeper issues [ESPN]

- Yes, social media and video games really can hurt footballers’ decision-making [The Guardian]

- Jesus Luzardo apologizes to Oakland Athletics for breaking pinkie playing video game [ESPN]

- The Leaders State of Play Series: The Evolving Mindset of the Modern NBA Athlete [Leaders in Sport]

- Video-game addiction derailing NHL prospect’s career: Report [Ottawa Citizen]

- Football stars go head-to-head over video games as coronavirus suspends play [CNN]

- From courts to consoles: With live sports canceled, pro athletes join the streaming surge [Washington Post]

- Seeing the benefits while trying to manage risk: Exploring coach perceptions and messaging with student-athletes around Fortnite [Sci-Hub]

Learn How Persuasive Design Is Used to Create Habit Forming Digital Media

Everything You Need to Know

Need Help? Reach out.

and digital media overuse treatment and education.

Our experienced and knowledgeable therapists can help.