Teen Suicide Study Identifies Gaps in Adult Digital Literacy as a Risk Factor

Dr. Brett Kennedy, Psy, D.

In This Article

What is Suicide Contagion and Why Does it Happen?

Terms to Know

Suicide Contagion: Copycat suicide

Suicide Cluster: Multiple suicides occurring in the same community and close together in time

Suicide Exposure: Learning of the suicide of someone you know, admire or can relate to

Colorado Youth Suicide Study: Kids Lacked Connection with Caring Adults

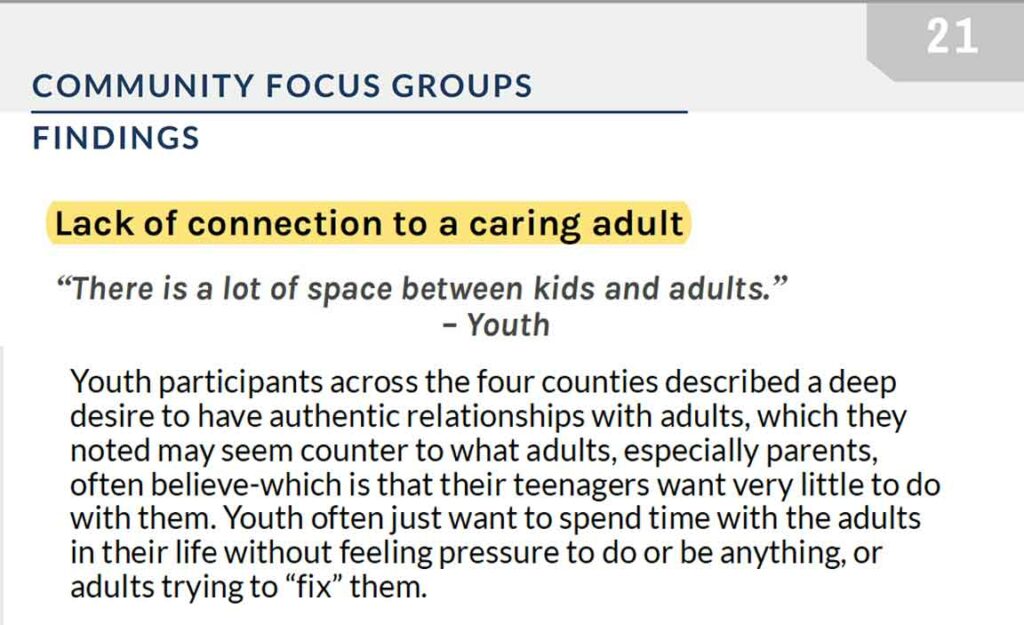

Kids described a culture where adults didn’t seem capable of sitting with children’s pain without trying to fix them or dismiss them.

Colorado, where I live, currently has the fifth highest suicide rate in the US and it’s consistently been in the top 10 since 2009.3

For 10- to 24-year-olds in Colorado, suicide is the number one cause of death.4

This is despite suicide prevention, postvention and intervention programs put in place to address the problem.

Many adults serving youth have been trained to spot signs of suicide.

They monitor teens after a stressful life event and recognize when there is a family history of suicide or suicidal behavior. Still the risk of suicide for teens remains higher here than in most other states.

After multiple youth suicide clusters happened in four counties between 2015 and 2017, the state attorney general initiated a study in those counties.

Central to the study was a series of interviews and focus groups with community members. The goal was to understand how these communities could better prevent suicidal behavior. As well as spot signs of teen suicide.

Teens and tweens, parents, educators, service providers, faith leaders and other stakeholders discussed why they believe suicidal behavior is occurring in their communities.

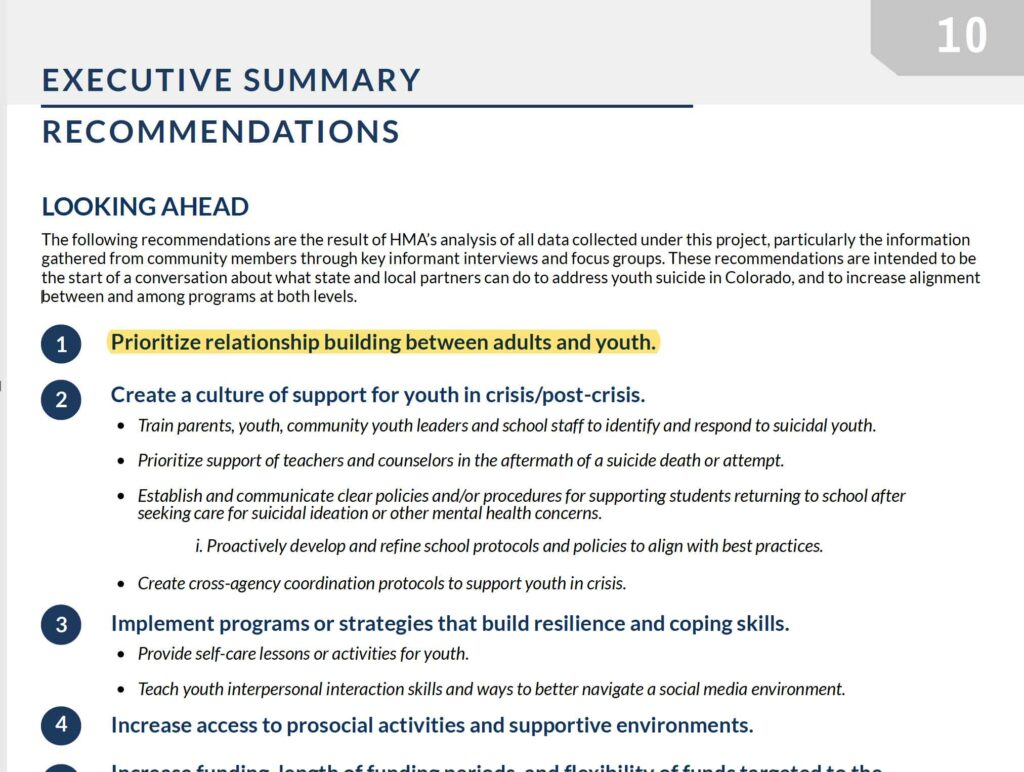

In the final report, the #1 recommendation researchers gave for moving forward was, “Prioritize relationship building between adults and youth.” 5

This is not to say that researchers didn’t list a plethora of logistical issues that should be addressed.

And by no means are we saying that there’s one solution to end all suicide attempts. Suicide is a complex, multi-faceted issue.

But before new suicide risk assessments or mental health interventions, across all four counties, researchers recommended that communities prioritize relationship building between adults and youth.

It’s important to note that the researchers also held focus groups in two control counties that had similar demographics, but no youth suicide clusters during the same period.

In those focus groups, young people said they had adults they trusted that they could talk to. And the local schools had a system in place that fostered adult-youth relationships.

By comparison, in the four counties with youth suicide clusters, across all socioeconomic backgrounds, kids said the adults in their lives were unable or unwilling to speak authentically with them about their problems.

This included adults at their schools and other institutions and organizations seeking to serve kids.

What did they mean by that?

Through various suicide prevention and mental health campaigns, kids were told repeatedly to reach out to an adult at school if they were depressed or anxious. But when they did, the conversation was quickly escalated to a crisis counselor for a suicide risk assessment. Usually, with a mental health professional they didn’t know or trust.

The adults in their schools were so traumatized by the frequent occurrence of suicide in their communities that they’d become overzealous about providing postvention support. Much of the time, the kids only needed a sympathetic ear from an adult in their school that they knew and trusted.

Another common occurrence, according to the kids in the study, was that parents would often minimize and dismiss their child’s cries for help as purely “attention-seeking.” (As if seeking attention is a bad thing.)

Kids described a culture where adults didn’t seem capable of sitting with children’s pain without trying to fix them or dismiss them. From the report:

“When it comes to discussing difficult topics, youth across all

communities shared that they do not often experience these

interactions as authentic or helpful. Youth are concerned that

adults will ‘freak out’ or overreact and not listen. They

expressed a wish that adults could just be with them in their

pain without jumping to assessments or solutions, but rather

just trying to understand. Along this same vein, youth groups

across each county expressed frustration that adults, most

often parents, tend to minimize their problems and pain. Youth

feel disheartened when adults tell them to ‘raise their voice’

or speak up about issues that concern them, but then shut

them down when they do raise their voice.”

Youth participants across the four counties described a deep desire to have authentic relationships with adults, which they noted may seem counter to what adults, especially parents, often believe—which is that their teenagers want very little to do with them. Youth often just want to spend time with the adults in their life without feeling pressure to do or be anything, or adults trying to ‘fix’ them.

— “Community Conversations to

Inform Youth Suicide

Prevention”, 2018 Colorado Study of 4 counties that experienced multiple, youth suicide clusters between 2015 and 2017, p. 7 and p. 21

This isn’t just the case in Colorado. On the popular podcast, “Teenager Therapy,” which is hosted by five teenagers in Anaheim, California, 17-year-old co-host Kayla revealed the hopelessness she felt when her mother reacted to Kayla’s request to go to therapy by minimizing Kayla’s feelings, saying, “you’re fine right now” and then asking Kayla why she didn’t pray. It’s worth watching the video clip below. The emotion in Kayla’s voice reveals the depth of her pain at her mother’s response and shows how easy it is for a parent to misread their child.

Kayla (17 years old): I think it just made me feel so… hopeless. Because in my house, I think ever since my sister left, my mom is the only one I can somewhat express my emotions to. And so, then, to hear her say that… it was so disappointing. I guess, like… I expected more. Which is my mistake, I guess.”

Thomas (17 years old): A lot of kids are reluctant to talk to their parents about therapy because, well, like that… they just wouldn’t understand. And, I don’t know…I just think it’s super unfortunate because if they can’t tell their own parents, then who can they tell? It’s really sad.

Gael (18 years old): People feel trapped. I mean, at least you’re close to 18 and you can do it on your own almost, but imagine being like 14, 15… like through the worst time of your life and you tell your parent, ‘I want to go to therapy.’ And they’re just like, ‘No, you can’t.’ You feel so hopeless, and I imagine it would just be like the sense of being trapped. It must be just so frustrating.

A lot of kids are reluctant to talk to their parents about therapy because … they just wouldn’t understand. And I don’t know… I just think it’s super unfortunate because if they can’t tell their own parents, then who can they tell? It’s really sad.

— Thomas

17-year-old co-host

Teenager Therapy Podcast

February 28, 2021

How the Parent-Child Bond Can Protect Against Depression & Anxiety

During adolescence, the attachment teenagers have with their parents begins to shift to include an attachment to their peers and to the outside world. This is normal and it’s a process that all mammals go through to prepare for adulthood. At the same time, adolescent brains are undergoing developments that cause them to move toward novelty experiences and risk taking.

It’s at this time that the parent-child bond is highly vulnerable to becoming strained. Teenagers are suddenly engaging in ill-conceived high jinks and they’re emotionally erratic to boot. But studies show that maintaining an attachment with your teen, even as the relationship evolves to look very different, is vital to their mental health.

One long-term study of adolescents published in 2018 predictably found that the quality of the parent-child relationship steadily declined starting in 6th grade. But interestingly, the amount of alienation, loss of trust and lack of communication the kids felt in middle school predicted the amount of depressive symptoms and anxiety they reported in 12th grade. 6

The study’s authors say this shows that, despite the push back teens give to assert their independence and autonomy, they still very much need their parents’ emotional support all the way through high school.

In the video below, one of the researchers from the study, Ashley Ebbert, emphasizes how important it is for parents to understand this subtle nuance of adolescent behavior.

“Even though adolescents are kind of gravitating more towards peers, they’re expanding their social network, they still heavily rely on parents—I think throughout middle school and high school—for instrumental sources of support. Especially as they’re getting ready to graduate and kind of go on to that next chapter, getting ready for college, things like that. I think they’re kind of clinging a little bit more onto their parents then parents assume.”

“Parents think to give their adolescent their space. Especially when they’re being kind of bratty and pushing back and, you know, there’s a lot of conflict in adolescent-parent relationships around the age of fifteen, sixteen, when they’re making that transition into high school.”

But, Ebbert says, “It’s still really important for them to kind of maintain close bonds with their kids through trust and communication as needed.”

Studies show that the more alienation and loss of trust teenagers feel towards their parents, the higher their levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Many Adults Are Overconfident About Their Ability to Read Kids

It’s not easy to know when kids are depressed or in need of more attention, even if adults think it is.

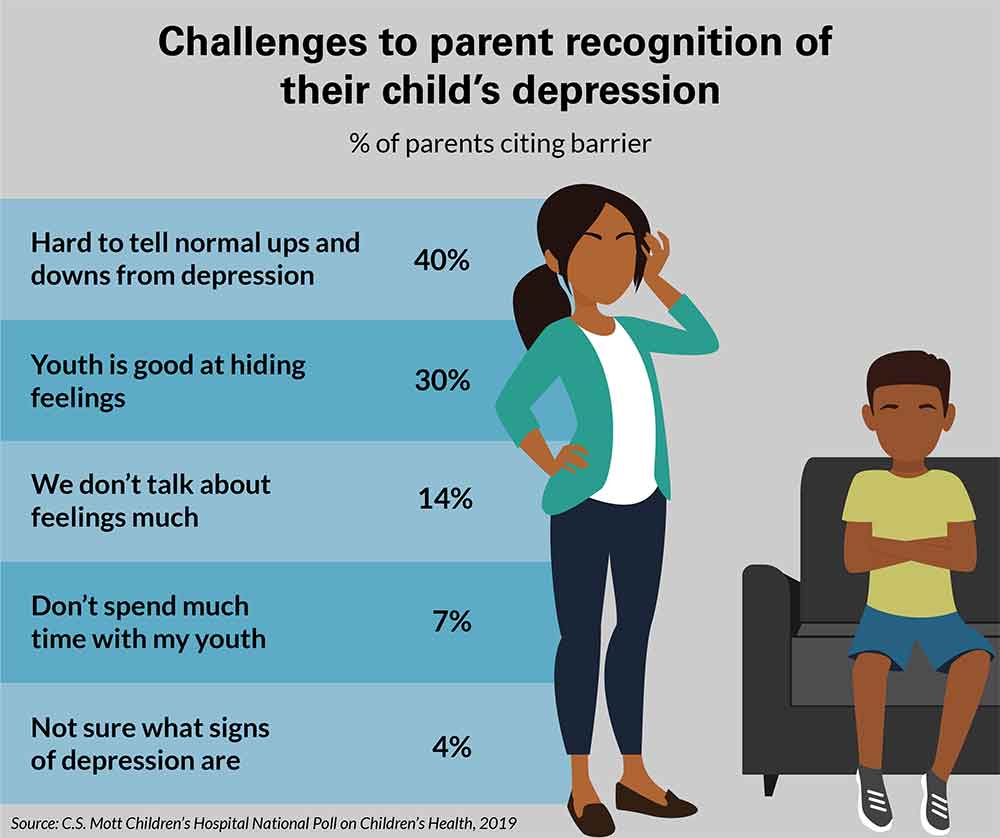

A 2019 nationally representative survey of parents by the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital at the University of Michigan found 90% of parents rated themselves as “confident” or “very confident” that they could recognize the signs and symptoms of depression in their children.7 But 2/3 of them cited barriers they may have in recognizing their child’s depression. Such barriers included difficulty discerning between normal ups and downs and possible depression (40%), and youth being good at hiding their feelings (30%). Less commonly cited barriers were youth not talking much about feelings (14%), parents not spending time with their children (7%), and parental uncertainty about the signs of depression (4%).

Teens Want Trusted Adults They Can Go to for Support

The kids that participated in the Colorado youth suicide prevention focus groups said that when they have established relationships with trusted adults, they will go to those adults for support when they need it. But building that trust requires time and a willingness and capacity to talk with them about difficult subjects.

Many parents in the Colorado youth suicide prevention focus groups, on the other hand, admitted to feeling unprepared to help their child who may be suicidal, or when their child comes to them for help with a friend.

Why Adults Need Digital Literacy to Build Relationships with Kids

Digital literacy means having the skills to use digital media so that you can live, learn, and work in the digital environment.

Most digital literacy articles and programs focus on the need for kids and teens to be digitally literate and become good “digital citizens.” Digital citizenship refers to the responsible use of digital technology.

But few raise the issue that those teaching digital literacy—adults—are often less digitally literate than the kids they seek to teach.

In the Colorado youth suicide prevention report, social media use was identified by adult and teen focus group participants as one risk factor for the high rates of teen suicide in their communities. Not because social media causes teen suicide. But because, along with the tremendous good that can come from social media and the internet, teens must navigate issues like cyberbullying. Additionally, teens can experience a loss of interpersonal social skills and an inability to take a break from constant interaction—especially negative interaction—on social media.

But interviewees in the study said that adults and institutions don’t know how to navigate the digital world youth are living in, and thus don’t know how to help youth build the necessary resiliency. The result, they say, is that young people are experiencing more social disconnectedness and isolation.

It’s in this context that we say gaps in digital literacy among adults is hindering their ability to connect with and guide youth. What’s more, it’s contributing to the prevalence of teen social disconnectedness and isolation which have been shown in studies to be positively associated with mental health problems (depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, stress, sleep problems, suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury, eating disorder, body dissatisfaction, and low self-esteem) and negatively associated with mental well-being.8

Once again, this is not an issue unique to these communities. In a Common Sense Media nationally representative survey of 2,658 U.S. children ages 8 to 18 years old, 30 percent of teens who use social media say their parents know “little” or “nothing” about what they do or say there, and 25 percent say the same about their internet use in general.9

Understanding social media and the digital landscape that children use is part of digital literacy.

Around the world, child advocacy organizations are calling for adults to become digitally literate. So that we can aid the younger generation in succeeding as future adults, not just professionally, but socially and emotionally, too.

Around the world, child advocacy organizations are calling for adults to become digitally literate. So that we can aid the younger generation in succeeding as future adults, not just professionally, but socially and emotionally, too.

In their white paper Digital Literacy and Citizenship in the 21st Century, Common Sense Media calls for a redesign of education to disseminate a basic curriculum that defines the standards of ethical behavior on digital platforms – for students, parents, and educators.10 With regard to the role of parents, it says.

“Parents desperately need to understand not only the technologies that inform their children’s lives, but also the issues around behavior and responsible use.”

Policymakers are too quick to assume that children and young people’s status as ‘digital natives’ reduces the need for digital understanding and have focused too narrowly on safety and risk. Digital literacy is often reduced to a set of ‘stranger danger’ messages that fail to engage students or reflect the realities of their digital use.

This ignores the fact that children’s and young people’s rights are balanced and multifaceted, entitling them to both autonomy over their own lives and development, and to participation in society more broadly. In an interconnected world, if children and young people’s rights are not upheld in one environment, they are denuded in all environments.

Policymakers are too quick to assume that children and young people’s status as ‘digital natives’ reduces the need for digital understanding and have focused too narrowly on safety and risk. Digital literacy is often reduced to a set of ‘stranger danger’ messages that fail to engage students or reflect the realities of their digital use.And

States parties should identify and address the emerging risks that children face in diverse contexts, including by listening to their views on the nature of the particular risks that they face.

With this growing prominence, we see that technology is beginning to shift the expectations that young people have around what makes a good friend.

In this survey young people told us loud and clear that they want their parents, carers, teachers and friends to help them with this.

Youth participants in the Colorado teen suicide prevention focus groups across every county communicated that they don’t feel equipped to help their friends, but they do have a desire to be trained in how to help. But how can kids be trained when the adults in their community know so little about the digital world they inhabit?Terms to Know

Digital Literacy: The skills to use digital media so that you can live, learn, and work in the digital environment.

Digital Citizenship The responsible use of digital technology.

A Checklist for Improving Digital Literacy & Becoming a Good Digital Citizen

Adults often feel overwhelmed at the prospect of taking on digital literacy. Where to begin? The Council of Europe has created the following checklist to break it down into steps. Their guide, Easy steps to help your child become a Digital Citizen contains tips to help you complete the items on the following list.14

- I know what sort of activities my children do online.

- My children know how to use search engines and compare results.

- My children spend a lot of their time online doing projects, homework, or exploring new things (for example, an online museum or eScience lab).

- My children create and share their own content.

- My children are good listeners and observers, able to understand the point of view of other people.

- My family takes time out from technology, switching off devices at mealtime or after a certain time at night.

- My children discuss with me the things that bother them online and any unpleasant content they come across.

- I know the online groups my children belong to, and the focus of these groups.

- My children show a healthy balance in the time they spend on face-to-face, physical and online activities.

- My children spend more time communicating face-to-face with friends than they do playing or chatting online, or watching videos.

- I sometimes sit next to my children when they go online, and we talk about how to use the internet responsibly and ethically.

- My children are aware of the sort of information they should keep private, and why.

- My children take an interest in talking about what they believe is wrong in the digital world, and ways they could help make things better.

- I know the main information sources and/or news channels my children use.

- My children are able to tell the difference between reliable and unreliable online information.

How to Start a Dialogue with a Teenager

In October of 2018, 15-year-old Robbie Eckhert of Colorado died by suicide. His parents, Jason & Kari Eckert, went on to found the organization Robbie’s Hope with the help of some of Robbie’s friends. The goal of Robbie’s Hope is to cut the teen suicide rate in half by 2028. Robbie’s Hope has published handbooks to help adults talk to teenagers about depression, suicide and technology use. All of the handbooks are written by teenagers and explain how teenagers want to be approached and addressed by adults.

In the introduction to their first publication, Robbie’s Hope Adult Handbook: A Guide by Teens on How to Talk to Teens, Robbie’s parents share their inspiration for supporting Robbie’s Hope teen activists to write it.

“We never knew that Robbie was struggling; we never asked. We assumed that because he was outwardly happy and successful that it reflected his inner feelings and emotions as well. Our single biggest regret in life is that we never had that conversation.” [Emphasis theirs.]

They go on to stress that the handbook isn’t just for parents.

“Many teens would rather have these conversations with other trusted adults: coaches, teachers, youth group leaders, mentors. Taking this first step may make the difference in a teen’s life.”

Here are some tips from the handbook:

- It’s important to have the conversation regularly, when there are no signs of depression or anxiety at all. Creating open dialogue will make the teen comfortable coming to you in the future.

- Make it a conversation between two people. Be prepared to ask lots of questions and listen, without interjecting your own advice. The teen wants to be heard, not told how to feel.

- Use a soothing tone of voice. Sounding loud or harsh may cause the teen to shut down.

- Be aware of your facial expressions and body language. The teen can sense disappointment and judgment based on your physical actions.

- Be ready for the teen to avoid the conversation. If they are not ready to talk, don’t force it. But don’t give up, either. Communicate your desire to find a better time and location to talk.

- Express your love and support. Reassure the teen that nothing they say will cause you disappointment or judgment. You can communicate this through both words and body language.

- Arguably, the most important aspect of proper technology use is engaging in the right kinds of conversations about it.

- Parents and trusted adults need to be able to have these conversations with their teens, about the good and bad that can come from technology use.

- Keep in mind, these discussions are a two-way street, not a lecture.

- The best approach for parents and trusted adults is to approach it from a framework of “Let’s learn together.”

- Be sure to start having these conversations as early as possible, so that expectations and open lines of communication are established before they become problems.

- Conversations between a parent/trusted adult and teen about technology should be ongoing and should occur at a minimum of once per month.

- For parents: Be open to allowing your teen to “call you out” and discuss concerns about your personal technology habits.

- For teens: Be open to allowing your parent to give you feedback about your technology use and have the courage to tell your parents when technology usage becomes an issue.

Links to Media Mentioned in this Article

- Robbie’s Hope Adult Handbook & Technology Handbook – Robbie’s Hope is a movement of young people working to normalize talking about their emotions and to remind anyone who’s struggling that they’re not alone and that It’s Ok To Not Be Ok. Robbie’s Hope was organized by teens for teens in honor of Robbie Eckert, who died by suicide in October 2018 at the age of fifteen.

- Teenager Therapy Podcast – Five stressed, sleep deprived, yet energetic teens sit down and talk about the struggles that come with being a teenager. Is high school really as bad as everyone says?

Other Resources on Digital Literacy & Understanding Teens

- What teens wish their parents knew about social media, article in the Washington Post from noted teen expert, author, speaker and educator Ana Homayoun

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Children (UNCRC) general comment on children’s rights in relation to the digital environment at 5Rights Foundation, an organization established in 2013 to promote the rights of children online. The UNCRC, is the basis of all of UNICEF’s work. It is the most complete statement of children’s rights ever produced and is the most widely-ratified international human rights treaty in history. UNICEF, also known as the United Nations Children’s Fund, is a United Nations agency responsible for providing humanitarian and developmental aid to children worldwide. The agency is among the most widespread and recognizable social welfare organizations in the world, with a presence in 192 countries and territories.

- Everything You Need to Teach Digital Citizenship, a free educational curriculum from Common Sense Media, a San Francisco-based, nonprofit organization that provides education and advocacy to families to promote safe technology and media for children.

- Help Me Understand Teenagers & Technology + Tips for supporting your teenager at ReachOut Australia, established in 1997 to harness the potential of the internet and

provide the world’s first online mental health service for young people - Top 10 Things Adults Can Learn from Teens about Social Media A blog post on the website of 826 National, the largest youth writing network in the US.

- Lesson: True Connections – Personal Experiences with Social Media Full lesson text and accompanying resources for grades 6-9. Invite students to write about their personal experiences with social media and online platforms with this lesson from 826NYC.

- Animal adolescence is filled with teen drama and peer pressure – Washington Post article about the book Wildhood: The Epic Journey From Adolescence to Adulthood in Humans and Other Animals by Barbara Natterson-Horowitz, a Harvard evolutionary biologist, and Kathryn Bowers, a science journalist, that explains how adolescence is nature’s way of preparing animals (including humans) for adulthood.

1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a, October). Death Rates Due to Suicide and Homicide Among Persons Aged 10–24: United States, 2000–2017. cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db352.htm#ref4

2. Forum on Global Violence Prevention; Board on Global Health; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Contagion of Violence: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013 Feb 6. II.4, THE CONTAGION OF SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207262/

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Suicide Mortality by State. cdc.gov. Accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/suicide-mortality/suicide.htm on Sep 18, 2021 12:15:15 PM

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2019 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2020. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html on Sep 18, 2021 1:21:48 PM

5. The Colorado Office of the Attorney General & Health Management Associates (2018). EXECUTIVE SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS: Looking ahead. In Community Conversations to Inform Youth Suicide Prevention: A Study of Youth Suicide in Four Colorado Counties (p. 10). The Colorado Office of the Attorney General. https://www.coloradovirtuallibrary.org/resource-sharing/state-pubs-blog/new-report-on-youth-suicide-prevention/

6. Ebbert, A. M., Infurna, F. J., & Luthar, S. S. (2018). Mapping developmental changes in perceived parent–adolescent relationship quality throughout middle school and high school. Development and Psychopathology, 31(04), 1541–1556. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579418001219

7. C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital. (2019, November). Recognizing Youth Depression at Home and School (Mott Poll Report: Issue 2). C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, the University of Michigan Department of Pediatrics, and the University of Michigan Susan B. Meister Child Health Evaluation and Research (CHEAR) Center. https://mottpoll.org/reports/recognizing-youth-depression-home-and-school

8. Santini, Z. I., Pisinger, V. S. C., Nielsen, L., Madsen, K. R., Nelausen, M. K., Koyanagi, A., Koushede, V., Roffey, S., Thygesen, L. C., & Meilstrup, C. (2021). Social Disconnectedness, Loneliness, and Mental Health Among Adolescents in Danish High Schools: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2021.632906

9. “The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens, 2015.” Common Sense Media, 15 Oct. 2015.

11. 5Rights Foundation. (2019, December 11). Data Literacy. 5rightsfoundation.com. https://5rightsfoundation.com/our-work/data-literacy/

12. 5Rights Foundation. (2019, December 11). Children and Young People’s Rights . 5rightsfoundation.com. https://5rightsfoundation.com/our-work/childrens-rights/

14. The Council of Europe. (2020, April 16). Easy steps to help your child become a Digital Citizen (2020). edoc.coe.int. https://edoc.coe.int/en/human-rights-democratic-citizenship-and-interculturalism/8169-easy-steps-to-help-your-child-become-a-digital-citizen.html.

Need Help? Reach out.

and digital media overuse treatment and education.

Our experienced and knowledgeable therapists can help.